How Russia Turns Gamers into Fighters

The Kremlin’s weaponization of video games for recruitment and influence is no longer a theoretical risk. To protect the digital commons, the West must treat gaming as a core frontier of contemporary hybrid warfare.

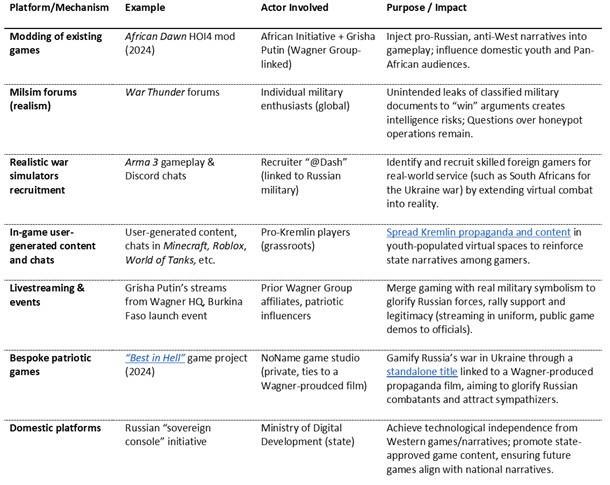

Russia’s active weaponization of video games has become ingrained in its doctrine of hybrid warfare, resulting in loss of lives across continents. Recent revelations from Bloomberg demonstrate how foreign nationals are recruited online via popular military-simulation (milsim) games and Discord chats to fight for Russia in Ukraine. These attempts fit neatly within broader influence operations and cognitive warfare tactics leveraging video games. From propaganda mods and in-game recruitment campaigns, to creating Russian-only sovereign gaming platforms, these tactics speak to the political and cultural reality of online games as contested information spaces. As previously assessed by RUSI, the immersive, interactive and transnational nature of modern gaming builds tight-knit social spaces with less moderation than conventional social media. Despite being perceived as apolitical, gaming ecosystems offer Moscow ample room to exercise hybrid tactics against audiences abroad. In effect, platforms designed for entertainment are converted into battlefields for influence and recruitment.

Recruitment from Gaming Spaces

In mid-2024, two young South African men fell victim to Russia’s gaming recruitment strategy. The pair, avid players of the milsim game Arma 3 and frequently present in related Discord servers, were approached by a recruiter using the handle ‘@Dash’. After weeks of conversation, this gaming recruiter arranged an in-person meeting in Cape Town, eventually a meeting at the Russian Consulate with officials. The pair were on a flight to St. Petersburg in July 2024, and by early September the gamers-turned-recruits had signed one-year contracts with the Russian military. Within weeks, however, one of the South Africans was killed in action in Ukraine. The episode has sparked a scandal in South Africa (where serving in a foreign army has been illegal since 1998) and exposed a clandestine pipeline for fighters recruited through gaming communities. South African political figures have also faced accusations of recruiting fighters for Russia.

What distinguishes recruitment in gaming from foreign legions or private military companies (PMCs) is its affordance of minimal state-level diplomatic fingerprints and greater plausible deniability.

Many elements of this case mirror those of terrorist radicalisation and recruitment; dynamics which have been extensively studied by the Extremism and Gaming Research Network and RUSI.

The Kremlin is instrumentalising and integrating gaming content into its broader cognitive and influence warfare toolbox

Firstly, recruiters capitalised on the military-themed gaming interests of the targets, effectively fishing in user pools already fascinated by combat and weaponry. In realistic milsim games like Arma 3 and War Thunder, the lines between simulation and real combat become hazy, in turn appealing also to active duty military players. This blurred reality is so acute that over a dozen gamers have leaked classified schematics of tanks and aircraft on War Thunder to prove how realistic, or not, the in-game depictions are.

Second, after meeting in Arma 3 or related chatrooms, the recruiters approached the targets via Discord, a massively popular community chat platform, where they could continue more private conversations. This practice, known as outlinking or off-platforming, is a well-established tactic: recruiters identify potential targets in public games (Roblox, Arma 3), move them to more private gaming chatrooms or groups (on Discord), and finally to end-to-end encrypted chats on Signal or Telegram. We saw this in the case of US Air National Guardsman Jack Teixeira, who leaked classified intelligence to his gaming friends on a Discord server. Teixeira’s case demonstrates the powerful trust networks built via gaming spaces, which, while often positive, create vulnerabilities to exploitation for recruitment, espionage and other hybrid warfare tactics.

Lastly, in the South Africa case, promises of material economic incentives were leveraged to ‘level up’ their gaming fantasies, with military service posing as an extension of the virtual combat game they loved. This is also not new: prior to its 2023 collapse, the Wagner Group explicitly tried to ‘draft gamers as UAV operators’ via social media posts. In 2022, Russia’s Defence Ministry also ran targeted ads to gamers with the slogan ‘play with real rules, with no cheat codes or saves,’ openly inviting players to join the army.

These efforts are partly driven by Russia’s urgent manpower needs. Having suffered heavy losses in Ukraine, exhausting conscription and prison-based enlistment, Moscow has intensified its search for fighters abroad, with at least 18,000 known foreign fighters having enlisted in Russian units. Instead of relying on conscription or civilian recruitment, Russia now targets foreign, young men in gaming spaces, exploiting economic grievances, social desires and gaming dynamics to turn online gamers into frontline fighters.

Gamifying Cognitive Warfare: Propaganda Games

Beyond clandestine foreign recruiting, Russia is investing heavily in gaming infrastructures. The Kremlin is instrumentalising and integrating gaming content into its broader cognitive and influence warfare toolbox. Moscow’s active and heavy investments into developing ‘patriotic’ video games reflect a deliberate strategy: to shape public and political perceptions, normalise militarised narratives, and win the ‘hearts and minds’, especially among youth at home and abroad.

Help your search results show more from RUSI. Adding RUSI as a preferred source on Google means our analysis appears more prominently.

Stay up to date with the latest publications and events from the Terrorism and Conflict Research Group

Under the auspices of the Internet Development Institute (IDI), a state-backed group tasked with youth-oriented internet content, Russia has poured billions of roubles into domestic game development. In 2022–2023 alone, IDI earmarked approximately RUB 2.5 billion (~ £25 million) to support domestic game developers creating ideological propagandistic titles. Games like Sparta, paying tribute to Russian PMSC and Wagner operations in Africa, and Front Edge, simulating a direct Russian-US clash in Eastern Europe, intend to normalise Kremlin propaganda and glorify war amongst domestic youth. While these games face domestic criticism and underperform commercially, their existence signals a deliberate strategy to weaponise gaming for cognitive warfare and saturate the information environment. Although largely unsuccessful and criticised, the risk of eventual success exists with continued investment and experimentation.

The Kremlin also funds patriotic game development abroad, including African Dawn, a modification of the popular game Hearts of Iron IV. In African Dawn, a game co-developed by Moscow-based African Initiative and a pro-Kremlin gaming streamer, players lead a coalition of Sahel countries (Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger) against Western influence. Its content aligns closely with Russia’s strategic narratives: projecting anti-colonial and Western narratives among young, digitally engaged African demographics. Although the player base is limited, press releases of African Dawn were done in multiple languages (English, French, Russian, Arabic), reinforcing Moscow’s strategic intent to weaponise anti-Western grievances and achieve narrative dominance both domestically and across the continent. In short, it ‘sets out Russia’s agenda for Africa – to increase its influence and discredit Western partners.’

Russian gaming propaganda echoes well-documented tactics employed by terrorist groups. By taking popular strategy games, embedding propagandistic narratives and contemporary geopolitical conflicts, and releasing them to targeted youth, Russian propagandists leverage the contemporary narrative power of games to substantial effect. This holds particularly true in a rapidly digitising Africa. Yet, while African gamers are the ostensible target audience, campaign strategists likely seek wider engagement within Russia and across the West. At home, it can galvanise nationalist youth and reinforce Russia’s ‘role’ as anti-(Western) colonial champions; while abroad, it can influence perceptions by attempting to reframe Western engagements across Africa as neo-colonial or imperialistic. In all cases, Moscow benefits.

Far from an anomaly, the South African recruitment case underscores sophisticated shifts in digital ‘grey zones’ and cognitive warfare. Three years ago, the Swedish Psychological Defence Agency’s handbook, Malign Foreign Interference and Information Influence on Video Game Platforms, reported: ‘the video game domain is ripe for scandals of a similar scale and impact to 2016 [for social media platforms].’ This recent case involving South African fighters is more than a reminder. It is a predictable manifestation of risks and warnings that have, until now, largely gone unheeded.

Drawing on recommendations to counter non-state violent extremists, there are four core categories, as collaboratively developed between RUSI, EGRN and the Global Internet Forum to Counter-Terrorism (GIFCT):

Design: Game developers, platforms, and publishers must integrate safety tools into games and gaming platforms pre-release to enhance early mitigation of exploitation by Russian actors.

Prevent: Governments and platforms must publicly name and denounce malign Russian influence and exploitation efforts, while simultaneously supporting gaming communities via positive interventions.

Detect: Law enforcement, military and intelligence agencies need in-depth knowledge of gaming spaces to identify, monitor and address this new frontier of hybrid warfare. This requires training, resources and multi-sectoral information sharing and collaboration.

React: Reporting mechanisms need to be simple, available and culturally adaptable; relevant for users reporting Russian influence operations and gamers falling (potentially) victim to Russia’s cognitive warfare and recruitment efforts.

Intervening in Russia’s weaponization of gaming ecosystems is both a tactical necessity and strategic imperative. If Western security agencies continue to view the gaming domain as merely an entertainment space, we risk ceding an important hybrid war surface to the Kremlin. It is vital to avert further recruitment of foreign civilians to fight and die on Russia’s frontlines, and to defend Ukraine and protect the international digital gaming commons from malicious exploitation and hybrid warfare tactics.

© RUSI, 2026.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the authors', and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

For terms of use, see Website Terms and Conditions of Use.

Have an idea for a Commentary you'd like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we'll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. View full guidelines for contributors.

WRITTEN BY

Galen Lamphere-Englund

RUSI Associate Fellow, Terrorism and Conflict

Petra Regeni

Research Analyst and Project Officer

RUSI Europe

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org