Lessons for the UK from Managing Grey Zone Hostility in Taiwan

Binary or ‘black-and-white’ thinking about the grey zone overlooks the disruptive effects of ambiguous sub-threshold activity.

The need to deal with hostile action in a ‘grey zone’ that is neither clearly peace nor war marks the return of an old problem rather than the arrival of a new one. It still needs dealing with. There are some new elements to be considered (for example, how information technology expands the attack surface), making a recently released House of Commons Defence Committee report, Defence in the Grey Zone, a welcome contribution.

Mike Mazar predicted in 2015 the rise of multipolarity and wider scope for putting revisionist motives into practice means grey zone campaigns ‘will constitute the default mode of conflict in coming decades’.

In 2016 Hal Brands pointed out, grey zone conflict demonstrates the weaknesses of the existing order. It shows how key revisionist states can nibble away at its edges, using incremental and subtly coercive approaches. It shows the limits of existing international security structures to prevent or reverse this coercive behaviour – as seen in the West’s struggle to undo, as opposed to simply punish, Russian aggression in Crimea and Ukraine.

In 2017, Nora Bensahel perceived that election of Donald Trump ‘may make it more likely . . . that the United States will face an increasing number of grey zone conflicts in the coming years.’ This is partly because of the President’s relatively ‘restrained’ foreign policy, and – in connection with Hal Brands’ point – Trump has ‘repeatedly expressed scepticism about international institutions and multinational cooperation.’

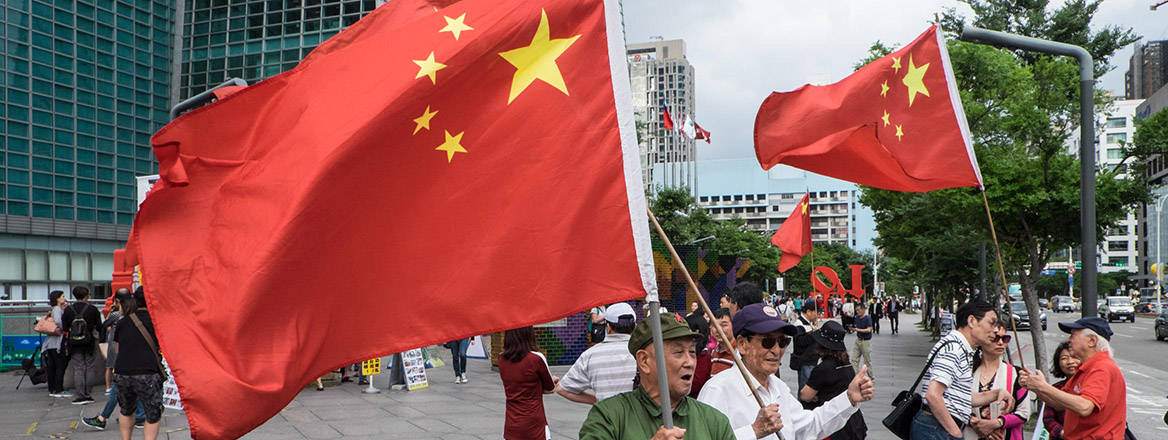

The committee drew evidence from across Europe (Finland, Latvia, the Netherlands), but this commentary recommends consulting like-minded partners further afield. RUSI’s ongoing research on Taiwan’s experience of dealing with hostility in the grey zone points to three insights that are complementary to the report’s findings, and which could contribute to continued cross-Government thinking on how to respond:

- Eliminate the ‘grey’.

- Address the cognitive trap.

- Turn the narrative from ‘escalation’ into ‘resilience’.

Eliminate the Grey

The first priority for managing hostile action in the ‘grey zone’ is to reduce the grey zone itself, by doing away with the ambiguities that create confusion on how to respond. This ambiguity takes two forms: disguised identity or intent of the hostile actor, and how the victim situates the act (and justifies the reaction) with reference to points on a spectrum between a state of peace and a state of war.

Identifying the hostile actor for public attribution demands investment in information collection, information flow management (within government and across the public / private interface), and intelligence. The Foreign Secretary’s statement on the China audit of an investment of £600 million in intelligence services is welcome news. Information flow also requires breaking silos and strengthening coordination functions under a well-planned strategic communication strategy. In March 2025, Taiwan’s President Lai made an explicit assessment that China is a ‘foreign hostile force’. On 16 June, he convened officials from the Ministry of National Defense, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mainland Affairs Council, and National Security Bureau to brief major opposition party leaders on national security issues.

Eliminating the ‘grey’ can be understood as like dialling up the contrast on an old black and white TV, allowing actions and reactions to be dealt with in the normal legal (white) category, or a ‘black’ category where laws and powers designed for states of emergency up to a state of war can be applied

Consistent with orthodox theory on grey zone warfare, the Committee report says ‘“Grey zone” refers to hostile activity below the threshold of direct, state-on-state conflict’, but this begs the question of where that threshold lies. In practical terms, it is a political decision. That decision should be made by the victim and not by the initiator of the action. Eliminating the ‘grey’ can be understood as like dialling up the contrast on an old black and white TV, allowing actions and reactions to be dealt with in the normal legal (white) category, or a ‘black’ category where laws and powers designed for states of emergency up to a state of war can be applied. Liberal democratic society is not naturally well adapted to a state of emergency, but to deal with the grey zone hostility, it needs constitutionally approved measures that safeguard values without offering loopholes for adversaries. Graduated mobilisation and sequential changes in rules of engagement need to be prepared in advance, in consultation with internal and external stakeholders. In March 2025, Taiwan launched a 17-point program that builds out the legal and institutional tool box to deal more effectively with hostile acts like subversion.

In the end, the defence committee concludes ‘current grey zone attacks indicate that Russia already believes it is in an existential struggle with the West,’ which takes the wind out of the debate on a meaningful formal ‘threshold’. This leads us to the next observation, which is that the obstacles to managing hostility in a grey zone are to be found less in the books of law and more between the ears.

Address the Cognitive Trap

Bureaucratic reform and capability requirements account for most of the committee’s recommendations. While they are important, the vital adjustment is cognitive; specifically, to a mentality that is prepared to enact a prompt comprehensive risk assessment that balances defence with other aspects of national interest. Such an assessment should be made with the resolve to accept there will be times to push back. In a landmark case, in June 2025, Taiwan jailed the captain of a ship – a Chinese national – that had been arrested on suspicion of causing damage to an undersea cable.

Ambiguity is only a good strategic position when the adversary believes you are prepared to act without perfect certainty about attribution. So long as the adversary believes you will not, you give him an incentive to do as much as possible while hiding his hand. In other words, you incentivise grey zone hostility.

As an illustration of the problem, the slowness and difficulty in responding to Russian ‘grey zone’ actions in 2014 lay not so much at a conceptual or organisational level, but in the low-risk appetite for escalation. Describing events in new terms such as ‘hybrid war’ and ‘grey zone’ perhaps made it easier to excuse the inability of the Kyiv government and its western supporters to mount an effective response. The reification of the ‘grey zone’ (the term is not part of Russian or Chinese doctrine), and fetishisation of ideas like a ‘Gerasimov doctrine’ and ‘hybrid war’ among Western commentators and theorists obscured more decisive – if unpalatable – factors: Ukraine’s poor organisational discipline, the West’s lack of commitment to deter or resist Russia and run the risk of escalation to a war for which they were materially unprepared and did not wish to fight.

Allowing the ‘grey zone’ concept to influence deliberation on policy choices can be counterproductive. Framing cable cutting as a ‘grey zone’ action rather than ‘sabotage’ endorses the difficulty of attribution and the significance of the attack ‘below the threshold’ of war. The choice to categorise such action as ‘grey zone’ may encourage the perpetrator to think they are less likely to be held accountable or punished, and they will consequently feel less deterred. Using the term ‘grey zone’ in ways that signal self-deterrence, lack of resolve or capability is a cognitive trap to be avoided.

In this context, the report’s approach to definitions suggests room for improvement. Noting that the term lacks a generally agreed definition, and that aspects overlap with other concepts such as ‘hybrid’ or ‘irregular warfare’, it resolves to use ‘the terms “grey zone” and “hybrid” interchangeably’, then suggests grey zone attacks ‘can be grouped, in an escalating level of hostile intent, as Influencing, Interfering, Operations and Conflict.’ This seems a muddle to say on one hand ‘grey zone’ refers to action below a certain threshold, but then to define it in a group that spans ‘influencing’ and ‘conflict’. ‘Operations’ could mean anything. To write (as the report does in the Summary) that ‘the scope is limitless,’ also does not help. Sabotage and assassination are attacks and must be identified and dealt with as such.

Action in the grey zone is designed to be morally asymmetric, in other words, the initiator disguises their intention or identity to cause the victim to hesitate to take effective action for fear of being accused of ‘escalation’

The report recognises the importance of a ‘willingness to use . . . capabilities either to deny or to punish those undertaking or authorising grey zone attacks’, but for a product of the defence establishment, its recommendations on what sort of capabilities are needed to inflict appropriate ‘punishment’, or how to help leadership determine when it is required, are strangely muted.

Reject the Narrative of ‘Escalation’ for One of ‘Resilience’

Action in the grey zone is designed to be morally asymmetric, in other words, the initiator disguises their intention or identity to cause the victim to hesitate to take effective action for fear of being accused of ‘escalation’. Failure to resist the narrative power of grey zone tactics can foster a sense of helplessness. To discredit attempts to blame the victim for trouble making and to gain the initiative, Taiwan’s government has promoted a narrative (with institutional backing) based on democratic and whole of society resilience. This allows moves that set strong positions pre-emptively, shifting the burden of escalation liability onto the other party.

The House of Commons report has a section entitled ‘building homeland resilience’, but here there is a glaring contradiction in this area of HMG policy. The former head of MI6, Sir Alex Younger told the committee of China ‘if you want a textbook on subversion, cyber and political harassment, it is all there’. Subsequently the UK China Audit ‘a full spectrum of threats – from espionage and cyber-attacks, to the repression of Hong Kongers, and attacks on the rules-based order . . . our protections must extend more widely than they currently do’. This grey zone report acknowledges ‘malicious foreign powers seek to influence the public debate, including on the war in Ukraine, by covert means, including influencing operations’, yet the government declined to list China on the enhanced tier of its new Foreign Influence Registration Scheme (FIRS). Ministers appear to support a request for China to open larger embassy premises, which would broaden its base to exert influence.

In this respect, Taiwan is well ahead of the UK. Despite the fact something near 40% of its exports go to China, the government in Taipei has tightened rather than shied away from measures to prevent subversion, espionage, and illicit influence from the PRC.

Conclusion

The ‘grey zone’ is not a fact of life to be accepted, but the natural consequence of a collective failure of commitment to upholding global order. As with any space neglected by order and enforcement, it is a hospitable base for predatory and unaccountable aggression. Developing capabilities and coordination is part of the solution, but ultimately it is more and unavoidably a problem of intellectual honesty and political confidence. The defence committee has done its part, but the government as a whole would do well to consult more widely on how to make the more UK resilient.

© RUSI, 2025.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

For terms of use, see Website Terms and Conditions of Use.

Have an idea for a Commentary you'd like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we'll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. View full guidelines for contributors.

WRITTEN BY

Dr Philip Shetler-Jones

Senior Research Fellow, Indo-Pacific Security

International Security

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org