Lessons from Bottom-Up Analysis of Crime, Terror and Insecurity in Africa

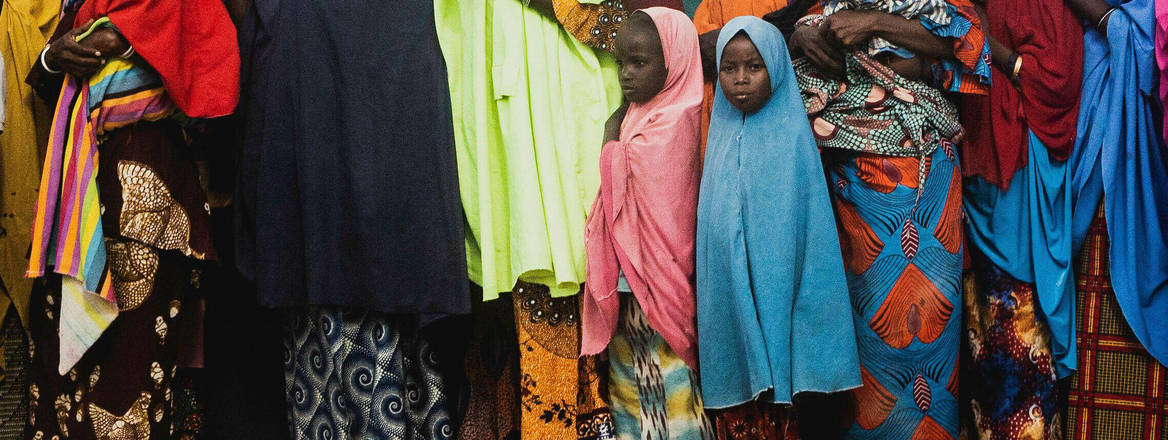

This Policy Brief presents practical considerations arising from RUSI's three-year project 'Organised Crime, Terror and Insecurity in Africa', which explores local perceptions and experiences of key security threats.

The link between crime and terrorism remains a priority for the global security community. Yet a significant proportion of relevant research is top-down, led by national and international bodies, privileging knowledge and responses at national and regional level. Local-level expertise and experience remains underrepresented, often to the detriment of effective responses.

As such, donor investment in tackling crime, terror and insecurity has, at times, been predicated on external assumptions that do not adequately consider the experiences of local communities or the individuals that make up those communities. This obscures crucial overlaps and interlinkages that inform the way crime, terror and wider insecurity manifest, proliferate and persist, increasing the risk of ‘doing harm’ in donor programming.

This Policy Brief is the final output of RUSI’s three-year project, Organised Crime, Terror and Insecurity in Africa. The project addresses a critical gap in current knowledge on subnational perceptions of insecurity, building the evidence base from the bottom up and preferencing local involvement, inputs and lived experience. It explores the following research questions:

- How are crime, terrorism and other forms of insecurity perceived and experienced at the local level?

- What are the mechanisms conditioning local insecurity?

- What are the implications for interventions by national stakeholders and international donors?

The project’s contribution is to complement conventional understandings of crime, terror and wider insecurity, which generally privilege government and donor perspectives, with bottom-up efforts that harness local knowledge, providing a more holistic appraisal of the threat landscape and contributing to more effective interventions. This Policy Brief draws on research conducted from 2022 to 2024 in two case study countries: Mozambique and Nigeria.

Primary research was conducted in Mozambique via 108 semi-structured interviews, one focus group and a verification workshop with local stakeholders spread across five locations. In Nigeria research was via 113 semi-structured interviews and a verification workshop across four locations, as well as secondary analysis. The findings are published in separate research papers, ‘Crime, Terror and Insecurity in Mozambique: A Bottom-Up Analysis of Local Perceptions’ and ‘Crime, Terror and Insecurity in Nigeria A Bottom-Up Analysis of Local Perceptions’. This Policy Brief also draws on learnings about the financial aspects of everyday insecurity published as a separate Policy Brief, ‘Financial Dynamics of Insecurity in Mozambique and Nigeria’.

In conducting this research, the authors acknowledge the complexities and limitations of researching crime, terror and wider insecurity in these contexts. The findings should not be viewed as a fully representative reflection of subnational perceptions, and are subject to contextual sensitivities, personal perspectives and imperfect information. Yet together they provide an authentic interpretation of ‘lived insecurity’ across specific moments and places – raising important considerations for national and international policy and programming.

Local Perceptions of Insecurity: Implications for Policy and Programming

The forms of insecurity described by local-level stakeholders were many and varied. Importantly, the research reveals that while individual manifestations of insecurity may appear to be discrete phenomena, many coexist as symptoms of the same wicked problem, the full scope of which must be considered for effective policymaking.

Often, the nature of insecurity as experienced on the ground is intrinsically linked to the sociopolitical architecture of any given location, the specific history of community engagement with the state in that location, and the parallel ‘informal’ norms, rules and inequalities that shape local behaviours and intersectional power dynamics. A deep understanding of these local realities is necessary to support sustainable change that addresses the drivers and real-life experiences of crime, terror and wider forms of insecurity.

Concerted engagement with the views and lived experiences of local communities is therefore paramount, as is recognition that communities are not monoliths but composites of individuals experiencing different realities. Specifically, external programming must be designed based on meaningful consultation that considers the interests and lived experience of local-level stakeholders.

This is in line with the Global Counterterrorism Forum’s ‘Policy Toolkit on The Hague Good Practices on the Nexus Between Transnational Organized Crime and Terrorism’, which stresses the need for ‘context-specific responses based on evidence-based research’, drawing on ‘inputs from all sectors of society’. This approach is key to efforts to establish links between seemingly disconnected risks and to identify plausible entry points for locally grounded interventions.

The following findings emerged from the research across Mozambique and Nigeria, with crucial implications for national and international policy and programming.

Finding 1

The way in which insecurity is experienced at local level is often more complex and amorphous than presumed by national and international stakeholders.

Subnational variations in perceptions of insecurity reflect a complex and dynamic landscape of actors operating in discrete ways, contrary to common oversimplifications of local players and their motivations. Understanding this nuance is important for addressing misperceptions about the structure of violent groups, the acts they perpetrate and their incentives, with significant implications for the mechanics, scope and goals of domestic and international interventions.

In the case of banditry in Nigeria, respondents described a dispersion (and transformation) of violent activity across rural contexts, enabled by the proliferation of illicit arms, a dominant focus on jihadism in urban areas and growing resource contestation amid long-running environmental pressures. The multiplicity of actors involved, and their ability to both splinter and mirror methodologies employed by terror groups, has fed into their national designation as terrorist organisations.

More nuanced policy is necessary to address the workings of these changing groups, their interaction with organised crime and violent extremism, and the evolution of their operating strategies. Notably, local stakeholders often expressed an inability to distinguish between terrorist and organised criminal actors, as well as the perpetrators of broader forms of insecurity. Meanwhile, women and girls were reported as being vulnerable to rape and gender-based violence by bandits and regional terror groups, and more generally to the operations of other threat actors. Counterterrorism (CT) strategies are often misapplied in these complex environments, with a range of consequences at local level.

There is also a tendency to homogenise violent conduct at this level. This is the case in relation to external definitions of violence associated with Boko Haram (a jihadist militant group based in northeastern Nigeria), undermining efforts to engage with the nuance of local contexts and the most pressing needs of local communities.

Indeed, Boko Haram presents a perpetual challenge to policymakers given the inherent fluidity of its membership and operations, resulting in diverse representations across different political narratives. Interviewees in the terror-aware states of Borno and Yobe expressed uncertainty over the agency of the group’s various factions and offshoots, and their culpability for violent acts at local level. At the same time, they shared valuable insights on discrepancies between the ethos, behaviour and methodologies of those acting under the definitional umbrella of Boko Haram. Some were reported to be more ‘aggressive’ and seen as opportunistic fighters with little understanding of governance systems or appetite for ideological persuasion. Others were considered more predictable, predominantly orienting operations against the Nigerian state and engaging in more reliable provision of services (such as education, healthcare and safety), with consistent governance structures.

Similarly, a failure in existing policy and programming to account for the diversity and evolution of groups engaged in petty crime and local gangsterism risks marginalising growing threats and disregarding their diverse impacts at local level. Respondents in Mozambique highlighted the range of manifestations of street-level insecurity in key locations – from unsophisticated and opportunistic operations to those conducted by ‘structured or organised groups with leadership’. Respondents also stressed the growing sophistication of actors involved in targeted kidnappings, with some casting them as ‘notable crime syndicates’ with economic power and the ability to manage a range of different criminal enterprises. Today these operations are marked by tight coordination and collusion with officials – with fear of the threat posed extending beyond targeted sectors of the business community to all segments of society.

Meanwhile, in both Mozambique and Nigeria, interviewees commonly signalled the threat from terrorism to be rarer in their quotidian experiences than other forms of insecurity. This in itself does not invalidate the far-reaching impacts of those threats, and communities are not always best placed to recognise and diagnose macro forms of violence. However, given the multiple and complex ways in which different threat types intersect, a national and international response that is overly focused on CT programming reflects a failure to address other core drivers and enablers of insecurity.

Understanding the perceptions of vulnerable groups (such as women, children and disabled persons) is also critical to dissecting the multi-layered features of the security landscape. These groups’ often silent or invisible experiences of different forms of insecurity can provide key insights into local-level patterns and perpetrators of harm. This can help to avoid oversimplifications and the use of siloed categories of security threats and actors. In addition, learning from the capacity for agency and strategic choices among vulnerable groups in navigating complex intersecting security threats is key to the development of targeted interventions to address the diverse spectrum of lived experiences of insecurity.

Finding 2

State actors can play a fundamental role in sustaining insecurity.

Interviewees across a range of sites stressed the ways in which state actors can contribute to insecurity at a systemic and individual level, both directly and indirectly. They also highlighted the contradiction that the state is tasked with providing security, including through the legitimate use of force.

Testimonies from fieldwork sites in Nigeria spoke to the many ways in which state actions can generate instability. For instance, the episodic imposition of blanket bans on fishing, cattle markets and motorcycle sale and distribution as a tool to disrupt terrorist and criminal outfits has undercut livelihoods for local communities. In addition, poorly enforced government-led security operations that harm local populations were reported to increase the risk of radicalisation and foster distrust in public institutions. A similar dynamic was identified in Mozambique, with militarised security operations in the north, combined with a reported lack of transparency, fuelling local-level unrest.

Chronic distrust and fear of local-level state security providers are amplified by endemic corruption, which both neuters response infrastructures and empowers pseudo-state structures, vigilante groups and criminal networks to leverage or compensate for the absence of government services and protections. In Mozambique, corruption risks across the wider criminal justice system were reported to feed into a culture of impunity that was easily weaponised by insurgent and organised criminal actors. These actors were often held to seize on pervasive corruption as a key narrative to recruit new members and legitimise their activities.

At the same time, experiences of corrupt practices and abuses of power varied from place to place and person to person, re-enforcing the importance to effective policymaking of subnational, intersectional, empirical data. Interviewees made clear the paradoxical role of state actors as both ‘helpers and harmers’ in the security landscape, with experiences of this varying according to intersectional identity factors, including gender. In some locations, the likelihood of arrest and prosecution was reported to be determined by the financial means of the accused rather than the nature of their offences, with the state perceived to not represent an authoritative and credible provider of security and protection from violence. Meanwhile, access to decision-making roles and processes was described as exclusionary – for instance, it was mostly out of bounds for women – and participants highlighted an urgent need for more transparent, participatory and decentralised governance.

Respondents in Mozambique frequently captured this duality in their depictions of state institutions. In multiple locations, police were credited with maintaining regular patrols, arresting thieves and fostering community relationships, while simultaneously preying on local populations via entrenched patterns of bribery and exploitation. Similarly, political elites were reported to both determine the nature of security service provision across key locations, and participate in corrupt networks, circumventing the law and using lower-level security actors to serve their own interests.

This lived experience of state-led insecurity has far reaching implications. At community level, perceived public sector ineffectiveness can endow non-state security provision – including vigilante structures – with some legitimacy or acceptance. At the same time, disparities in access to private security services were cited as fuelling resentment, with moral quandaries raised where those unable to afford these services are left to live with insecurity.

Where private security is inaccessible, and state-based security provision is absent, respondents in some locations in Mozambique cited the role of community members in defensive action against suspected criminal perpetrators. This practice of self-protection from security risks was described as a pragmatic form of self-defence against broader lawlessness. Across subnational contexts, a spectrum of action was described, from well-structured systems of local-level protection to less organised, impulsive expressions of public anger at perceived public service failings, escalating at times into retaliatory violence against police officers and infrastructure.

In practice, this commodification and diversification of security provision means that security sector support or reform interventions that de facto see the state as a monolithic entity and principal security provider do not effectively engage with the realities of key subnational contexts. A programmatic focus on state security actors, often through a narrow focus on training, reflects technical assumptions that reduce the issues above to matters of capacity. This disregards the deeper complexities of many local political economies and risks triggering unintended consequences.

Finding 3

The boundaries between licit and illicit spheres of activity remain porous, fluid and highly subjective, with implications for insecurity as experienced at local level.

The presence of the state appears uneven across subnational locations in the focus countries. Where local communities have limited access to effective security provision by public authorities, informal actors – guided by equally informal norms – may dictate service provision mechanisms and decision-making.

The spectrum of informal activity in this space is wide, including a range of economic, protection, survival and livelihood strategies developed within communities to navigate security threats. These strategies and coping mechanisms also vary across different groups in response to specific needs, vulnerabilities and identity factors (such as gender, age, ability and class) and related inequalities.

At the same time, interviewees regularly alluded to the engagement of state actors in informal activity, as well as their involvement in a range of illicit economies. In Mozambique, for example, interview testimony revealed deep-seated concerns over elite dominance not only of key sectors of the legitimate economy, but also of a range of illicit economies – from drugs to illicit natural resource flows. Here, popular discontent centred often on perceived state actor control of the proceeds of crime generated by the range of large-scale trafficking flows to which the country plays host, with community actors perceiving themselves to be excluded – by high-level state actors – from any of the perceived economic benefits.

Distrust in state institutions was held to further legitimise local-level involvement in criminal activity. In this environment, actors at both the community and state level were held to participate in both the licit and illicit economies. Community members may, for instance, expend profits earned in the licit economy on products and services provided by (legitimised) informal actors – such as security and public goods. In this domain, ‘informal’ security providers may also be controlled or led by individuals holding posts in state institutions. The result is a blended economic environment, one in which political elites exercise power over both legal and illegal commerce.

Considerations such as these bring into question common donor approaches, including the tendency to default to national-level state partners in programming, predicated on the assumption that ‘good outcomes’ dissipate evenly, and that the solution lies in the ‘formal’ sphere.

Assumptions about the separation between licit and illicit economies further speak to a disconnect between donor assistance frameworks and the survival economics that characterise many local contexts. These assumptions also disregard the wider spectrum of informal activities, protection and livelihood strategies that do not fall clearly within the licit–illicit binary logic.

- For instance, community members may provide security through patrolling the local area, protecting their households and organising forums to discuss security issues and how to overcome them. The prevailing international notion is that it is the state which holds the monopoly on security provision; however, in many of the locations considered in this research, the state is discredited and viewed as ineffective as a security provider. Meanwhile, informal (predominantly male) security providers may be perceived as effective to pockets of community occupants, while simultaneously representing a threat to others. This adds yet another layer of disconnect between common donor responses and local-level concerns.

Finding 4

Do-no-harm principles are at risk when community perspectives are insufficiently considered.

While recognising widespread corruption among state providers of security, donors can often struggle to incentivise real behavioural change among political elites. In this context, there is a risk that support for state security infrastructure and (disjointed) criminal justice sector reform programming overlooks or infringes on the interests of local communities and the individuals within them.

This raises questions about donor capacity to address political and governance issues as direct and indirect drivers of insecurity, as well as the practicalities of ensuring they ‘do no harm’ amid the complexities of local political economies. Such issues arise, for example, where armed forces are accused of facilitating illicit trade and suppressing fundamental freedoms, yet continue to receive international support, in the name of CT. These challenges are exacerbated where quantitative targets ingrained in project evaluation metrics bear little resemblance to local-level needs. In certain cases, these difficulties may allude to a failure to invest in ‘thinking and working politically’, where international stakeholders prioritise technical solutions focused on formal structures over deeper engagement with politically feasible, community-oriented interventions.

These issues are not ubiquitous across the implementation landscape. The emergence of and continued focus on ‘do no harm’ principles is evidence of the evolution in donor thinking over time. There is, however, a need for greater nuance and realism in donor ambitions and theories of change, recognising the longstanding, complex and place-based nature of key drivers and enablers of insecurity. More can be done to identify entry points that speak to context-specific challenges and intersectional lived experiences of insecurity.

Conclusions

These findings offer a glimpse of the deep and complex interlinkages between different forms of insecurity as perceived primarily by community actors. They make clear the need to better integrate local insights into development assistance frameworks. They also highlight the need to recognise the role of state actors, at times, as enablers of violence, and the importance of engaging with longstanding inequalities, de facto informal rules, and non-state actors shaping alternative protection services or survival strategies across local communities.

Participatory, locally-led policymaking and implementation require more direct engagement with political realities and individuals at this level. Although complicated, this is necessary for any intervention to contribute to effective and sustained processes aimed at supporting long-term stability.

Recommendations

- National and international policy and programming should be informed by empirical data on local perceptions of insecurity. This is all the more important in a context of widespread distrust in state structures. Top-down programming must be balanced by a stronger focus on the diversity of lived experiences and underlying drivers of insecurity at the local level. An understanding of how different vulnerable groups experience violence and insecurity, and develop survival strategies, is key to more inclusive programming.

- National and international policy and programming should be formulated based on local-level manifestations of insecurity, rather than national legal (and Western-centric) definitions of terrorism and organised crime. This is key to addressing often complex, varied and amorphous expressions of insecurity at the local level, and the blurred lines between licit and illicit activities. Tailored and contextualised responses are vital for formulating better integrated policy and programming which speak to specific drivers of insecurity in key locations, as opposed to preconceived assumptions detached from local-level realities.

- National and international stakeholders should ground all action in rigorous intersectional gender-sensitive political economy analysis to identify and respond to specific underlying drivers of insecurity and enable longer-term impact at community level. This work should identify specific subnational systemic factors enabling continued insecurity, generating a more robust evidence base on the fluidity of threat actors and local-level power and influence structures, illuminating context-specific pathways for change.

- International stakeholders should ‘think and work politically’, responding to the realities of state capture and corruption, the operation of perverse incentives, and the historical drivers of institutional fragmentation and instability in particular contexts. They should be mindful of the importance of incremental reforms to support a gradual change in the status quo and the limitations of ‘technical fixes’. Options should be explored to deliver assistance through decentralised structures, based on in-depth analysis of the relevant political economies.

- International programmers need to conduct more consistent and reflective reviews of the externalities and potential unintended consequences of key initiatives. They must recognise the coexistence within host government structures of contradictory economic and political rationalities, as well as the dependencies between licit and illicit structures across key locations. Policy and programming must remain sensitive to these realities, ensuring that interventions account for context-specific drivers of illicit behaviour, nested in wider efforts to support more participatory and decentralised governance.

This interactive summary draws on extensive fieldwork conducted from 2022–24 in two case study countries: Mozambique and Nigeria giving voice to some of the main themes and perspectives raised, in the words of research participants themselves.

WRITTEN BY

Mark Williams

Programme Manager | SHOC Network Member - Researcher

Organised Crime and Policing

Pilar Domingo

Guest Contributor

Cathy Haenlein

Director of Organised Crime and Policing Studies

Organised Crime and Policing

Michael Jones

Senior Research Fellow

Terrorism and Conflict

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org