Operation Rising Lion: The First 72 Hours

Operation Rising Lion has demonstrated the vast conventional superiority that Israel enjoys over Iran, highlighting the importance of intelligence, surprise and effective air and missile defence. But for now, the impact on Iran’s nuclear programme is more uncertain.

When Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced that Operation Rising Lion had begun in the early hours of 13 June, he was declaring war and putting into action Israeli military planning years in the making to launch the largest attack on Iran since the 1980-89 Iran-Iraq War.

In an operation that is reported to be planned to last week, these are the early moments. Much is unclear, but some early deductions can be drawn from the first 72 hours of exchanges between Israel and Iran.

Ambitious and Sweeping Operations

The size of the operation dwarfs any previously attempted, with the first 24 hours reportedly involving over 200 combat aircraft striking over a hundred targets. Videos released by the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) show a range of aircraft involved in the operation, including F-15I, F-16I and F-35I.

While the stated target was the Iranian nuclear programme, the initial wave of attacks struck a much broader range of targets, including Iran’s military leadership, conventional military sites (including both ballistic missile production and storage) and air defences.

In something close to a decapitation of the Iranian security state, the Commander in Chief of the Iranian military, the Commander of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), the head of the IRGC’s Aerospace Forces, and the former head of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council (involved in talks with the US) were all killed, along with dozens of other officers and a number of senior nuclear scientists.

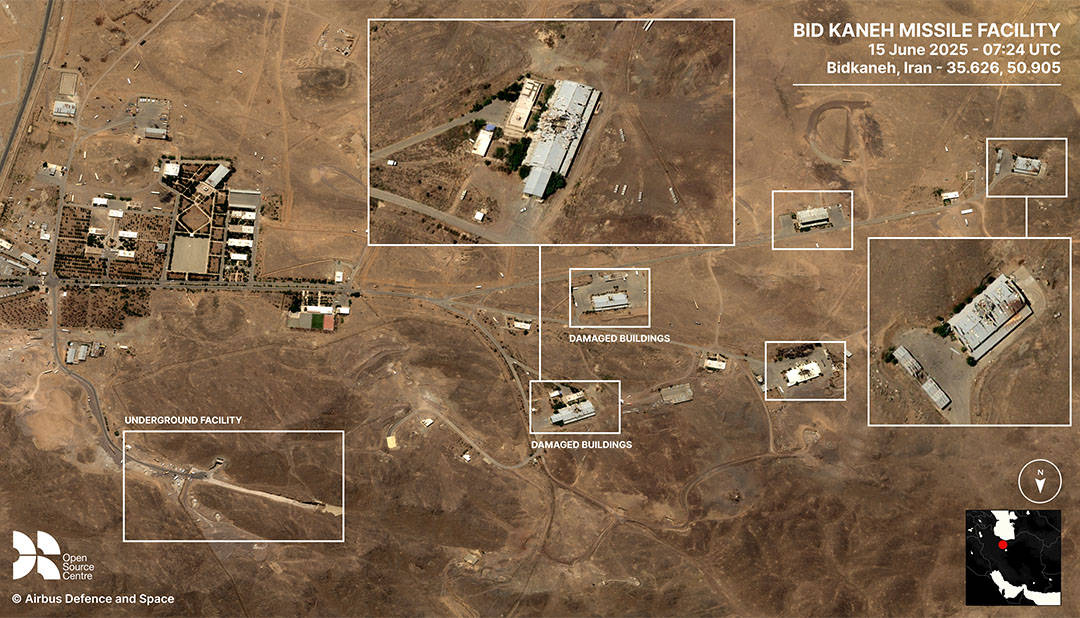

Conventional targets in the initial phase included ballistic missile launch sites and airbases near Tehran, Kermanshah and Tabriz, as well as air defence sites located across western Iran and around Tehran.

The following 48 hours saw smaller operations – but still involving around 50 aircraft for each wave of attack – and more strikes on Natanz alongside a number of other nuclear sites. By 15 June Israel had struck over 250 targets, and launched new attacks on Iranian energy infrastructure, especially oil and gas facilities, as well as government targets, reportedly including the Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS) in Tehran.

The Shadow War Becomes Open War

One of the most striking elements of the whole operation was a complementary covert Mossad operation to insert commando teams and weapons into Iran. This allowed them to launch missiles remotely, and loitering munitions/drones ahead of or in coordination with the incoming Israeli attack aircraft, destroying air defences to make their job easier, as well as striking ballistic missile launchers before they could participate in the Iranian retaliation. The video released to showcase this stunning operation was a demonstration of Israel’s success in building up and sustaining a covert action network in Iran over several years, last seen when Ismail Haniyeh was assassinated in Tehran in July 2024.

Strikes on Nuclear Sites and Assassinations of Scientists

The extent to which Israel has succeeded in undermining the nuclear programme is not yet clear, though the attacks carried out thus far are not sufficient to deal a decisive blow.

The Natanz nuclear complex sustained serious damage on the first day of strikes. The above-ground part of the Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant (PFEP), as well as electrical infrastructure at the complex, have been destroyed. The PFEP is one of three enrichment sites in Iran. As of May, the above-ground part of the facility was being used for R&D as well as for enriched uranium production, including with advanced centrifuge models, using three production-scale centrifuge cascades.

The facility was one of the sites being used for the enrichment of uranium to 60% uranium-235 – near the levels that are normally required for use in nuclear weapons.

There has thus far been no confirmation of any damage to Iran’s largest enrichment facility, the Fuel Enrichment Plant (FEP), also located at Natanz. As of May, the FEP hosted 101 centrifuge cascades (82 operational) and was used for enriching natural uranium to 5% uranium-235. The facility is located underground; satellite imagery has not shown any strikes on the site. A sudden loss of power (resulting from the destruction of electrical infrastructure) or vibrations from strikes in the vicinity could have also caused damage to the centrifuges inside the FEP.

Iran’s third enrichment facility – the Fordow Fuel Enrichment Plant (FFEP) – is buried deep underground, roughly 80-90 meters by some estimates. The facility hosts 16 installed (13 operational) cascades and plays a critical role in Iran’s production of fissile material. It is the primary site for the production of uranium enriched to 60% uranium-235, using advanced (IR-6) centrifuges and a 20% enriched uranium feed. This makes the FFEP central to Iran’s nuclear programme as the most hardened site, producing the greatest amount of highly-enriched uranium and with greater efficiency than its other facilities.

While Israel targeted the Fordow site on Friday, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) confirmed the following day that no damage has been observed at the FFEP. Indeed, penetrating a facility as deeply buried as the FFEP is likely to require the use of heavy-penetrating munitions like the American GBU-57/B and would be predicated on US involvement in the strikes.

Besides Iran’s uranium enrichment sites, Israel has also struck the Isfahan Nuclear Technology Centre, damaging the Uranium Conversion Facility (UCF) and the Fuel Plate Fabrication Plant (FPFP). The UCF, among other things, produced uranium hexafluoride for enrichment. The FPFP produced fuel for the Tehran Research Reactor and thus received at least some of Iran’s enriched uranium stocks. Both sites hosted capabilities for uranium metal production – a process key for the production of the core of a nuclear weapon; in 2021, uranium metal enriched to 20% had been produced at the FPFP.

In addition to Iran’s nuclear installations, Israel has also gone after Iran’s nuclear expertise, assassinating more than a dozen Iranian nuclear scientists as of Sunday evening, and the headquarters of the Iranian nuclear organisation (SPND). There have also been some reports of strikes near Parchin – a military complex where Iran is believed to have previously conducted weapons-relevant activity – though the nature of the strikes or extent of any damage is unclear.

Iran Strikes Back…to Little Effect So Far

For its part, the Iranian response (‘Operation True Promise III’) has been more limited than the Israeli strikes, both in terms of effectiveness and scope.

An initial response of around 200 drones (probably Shahed-136) launched in two waves appears to have been almost completely defeated by Israeli ground and air-based defences.

Subsequent drones launched piecemeal have met a similar fate, with Israeli defences bolstered by US forces (both a destroyer at sea and a THAAD battery based in Israel).

Ballistic missile strikes have followed, predominantly aimed at Jerusalem, Tel Aviv and Haifa. These have come in three main waves, with around 100 in the first strike, followed by several other smaller strikes. IDF officials in various media briefings on 15 June said these amounted to around 280 to nearly 300 ballistic missiles. This compares with just under 200 launched in a single night in Iran’s attack on Israel in October 2024. Around a dozen appear to have penetrated Israeli air defences, causing casualties, with perhaps a further 50 left unengaged by air defences, according to the IDF, as they were striking empty ground or non-vital targets. That leaves around 90% intercepted, most probably by Arrow 2 and 3 missiles, including some outside of the atmosphere.

Planning and Preparation Prevents Poor Performance

This is the war for which Israel has been planning for over two decades, and notwithstanding the question of political-military objectives, the effects are clear to see.

Firstly, the element of surprise and first-mover advantage, underpinned by effective intelligence, are obvious. Israel has been able to engage at a time and place of its choosing, and the extensive intelligence preparation it appears to have conducted have enabled precise timed operations.

Striking static nuclear sites is one thing, but identifying a series of leadership figures and being able to track and kill them near-simultaneously demonstrates extensive intelligence penetration of the Iranian system and, we might infer, real-time intelligence able to ‘fix’ their locations

Striking static nuclear sites is one thing, but identifying a series of leadership figures and being able to track and kill them near-simultaneously demonstrates extensive intelligence penetration of the Iranian system and, we might infer, real-time intelligence able to ‘fix’ their locations. This also extends to the claim that the Israelis knew how the senior leadership of the IRGC Aerospace Forces would react in a crisis and could therefore time a strike to kill as many as possible. The ability to prepare and mount covert operations inside Iran, allegedly including the manufacture of drones in-country, is just another example of the effort in long-term covert action paying-off.

The second visible effect of long-term planning is the obvious advantage conveyed by achieving air control, or in this case, air superiority (and the related importance of air defences).

The fact that strike aircraft appeared carrying direct-attack weapons like JDAM as part of the attacks on the first night explains why so many of the strikes hit targets other than Natanz and suggests the Israelis achieved air control early on (aided by the Mossad operation and presumably F-35Is hitting air defences in the first wave). Suppression of Enemy Air Defences (SEAD came from a variety of sources and has opened up incredible freedom, to the extent that Israeli Heron drones have now been seen operating freely in Iranian airspace.

Thirdly, integrated air and missile defence is both vital in modern warfare and difficult. The near-total collapse of any effective Iranian air defence, identified as a weakness in advance – even after the warning from Israel last year – has critically undermined the Iranian response so far.

Conversely, Israel has the most extensive layered air-defence system in the world, boosted by the US and combined with an early warning system, prepared-procedures for civilian protection with bunkers and shelters, all of which give it resilience and thusly greater freedom.

Even this system, protecting a relatively small geographic area, is not infallible. So, Israel has sought to conduct an extensive interdiction campaign, striking Iranian launchers and storage sites before they can be put into operation, as well as the initial disruption of IRGC Aerospace Forces’ command and control. It has become popular to talk about ‘shooting the archer, not the arrow’; if Israeli claims that Iran intended to launch hundreds of ballistic missiles in its initial retaliation are even half accurate, then this is an example of the impact of successful interdiction.

Limited Setbacks to the Nuclear Programme

The impact on Iran’s nuclear programme and implications for Israel’s strategic objective of reducing the threat of a future nuclear-armed Iran are less clear.

Israel has managed to cause meaningful damage to Iran’s ability to produce fissile material and to other weaponisation-relevant activities by destroying the PFEP, the UCF and FPFP. The assassination of senior scientists will no doubt also complicate and slow any efforts to reconstitute the programme or to push towards weaponisation

It is worth considering what the last 72 hours have done both to Iran’s technical capabilities as well as to Iran’s political resolve and threat perception.

On the former, Israel has managed to cause meaningful damage to Iran’s ability to produce fissile material and to other weaponisation-relevant activities by destroying the PFEP, and damaging the UCF and FPFP. The assassination of senior scientists will no doubt also complicate and slow any efforts to reconstitute the programme or to push towards weaponisation. Any impact on existing enriched uranium stocks is unclear. As Iran is estimated to be about a week from being able to enrich sufficient uranium to necessary levels to produce multiple nuclear weapons, destruction of fissile material and Iran’s ability to produce it will be a key to pushing back Tehran’s ability to produce a nuclear weapon.

However, the attacks have not decisively degraded Iran’s technical ability to weaponise its programme – nor are they likely to. The destruction of the FFEP and the FEP would set the Iranian capabilities and any weaponisation ambitions back even further; yet, the highly advanced state of the programme, including extensive technical expertise (which does not hinge on a small group of senior individuals) means that one can only talk about degrees of degradation and buying time, rather than the full elimination of the programme.

It is also unclear whether and what kind of activities Iran may be engaging in at any secret facilities which may be relevant to any weaponisation ambitions and the extent to which these sites are known to – and reachable by – Israel.

In fact, the attacks risk having a counterproductive effect when it comes to Iran’s threat perception and its resolve to arm itself with a nuclear weapons capability as the ultimate deterrent. Already, even before the strikes, Iranian leadership was threatening to withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT); over the weekend, Iranian legislators put forward draft legislation for NPT withdrawal.

NPT withdrawal . . . would be a risky move for Iran – particularly at the moment – as it would risk further attacks by Israel and potentially the US at a time when Iran’s capabilities to defend itself and retaliate have already been degraded. However, in light of the violence of the last few days, Tehran may decide it has little left to lose

Iranian leadership has also said that it will stop cooperation with the IAEA and curtail the Agency’s access to its programme, though the precise nature of any decrease in engagement with the IAEA is still unclear. NPT withdrawal would most likely result in a complete loss of IAEA visibility on Iran’s nuclear activities. Such a decision to withdraw would be a risky one for Iran – particularly at the moment – as it would risk further attacks by Israel and potentially the US at a time when Iran’s capabilities to defend itself and retaliate have already been degraded. However, in light of the violence of the last few days, Tehran may decide it has little left to lose.

Iran Caught Unprepared and Weakened

Conversely, the initial phases of this war show Iranian failures to plan and adapt, and the hollowness of its military strategy. It would be a mistake to regard Iran as a paper tiger, but it has not adapted to changing circumstances, nor spent time compensating for its conventional vulnerabilities in the same way Israel has over the last decade.

Israel introduced F-35Is in 2016 to improve its ability to penetrate air defences, and introduced the Rampage missile in 2018 to increase its standoff distances from other aircraft. It has been rehearsing long-range operations for years, and augmented its ability to support such attacks with not only long-range tankers but conformal fuel tanks for combat aircraft to extend their range. It is also easy to forget that with Lebanese Hizballah vastly weakened and Assad gone in Syria, the flightpath to Iran has become less complicated and dangerous.

By contrast, Iran has seen its position eroded over the past two years. Without proxies to launch weapons in large numbers from multiple angles at relatively short distances, slow-moving Iranian drones and cruise missiles pose a limited threat to Israeli targets 1000km away.

That leaves a reliance on ballistic missiles, but whereas Israel has both the intelligence and the weapons to precisely target specific parts of individual buildings, Iran lacks the intelligence and surveillance capabilities to do so. Despite accuracy improvements in newer missiles the bulk of its medium-range ballistic missile arsenal is still comprised of missiles like the Shahab-3, hence it is reduced to area-effect attacks. Iran can pose a significant regional threat, but not one with tactical precision to strike individual targets.

This operation is not just an attack on the Iranian nuclear programme; it’s a full-blown assault on the pillars of the Iranian security state, and an attempt to destabilise the Iranian regime

More directly, Iran has failed to plan or at least adopt crisis measures. Not only was it late to disperse personnel and enact improved security measures, but it also appears to have not dispersed some of its weapons, leading to potentially large numbers of ballistic missiles being destroyed in warehouses.

Iran has no emergency procedures in the face of Israeli air attack – even though it is the most likely form of attack – and so no structured early warning or civilian shelters, even in Tehran. Iran’s strategy has been based on appearing threatening enough to cause damage so as to deter an attack.

Israel’s deterrence has also failed, but whereas it is able to then wage a conventional war, Iran appears to have given itself few options.

Tell Me How this Ends

This operation is not just an attack on the Iranian nuclear programme; it’s a full-blown assault on the pillars of the Iranian security state, and an attempt to destabilise the Iranian regime. We don’t just need to infer this from the target choices: Netanyahu has said as much. It is unclear how brittle the regime is, but the course of the war so far leaves little doubt that Israel can strike most of western Iran and Tehran with impunity.

It is at this point though, that the uncertainties around the feasibility of the political-military objectives intrude. Much depends on what remains of Iran’s ballistic missile stockpile set against Israeli air defence interceptors. If the former runs out, then Iran has to escalate elsewhere, hunker down and take further punishment, or concede. If the latter occurs, then Israel will start to take hits which could become politically dangerous for the government.

Israel appears to be planning continued air strikes, and could be considering further unconventional activity. Tel Aviv has reportedly asked the US to get involved in strikes on the nuclear facility in Fordow, which would deal a significant blow to Iran’s enrichment capacity. Iran’s proxies have been largely silent, but it could still strike other western bases across the region (many less-well defended against air attack), or mine or otherwise seek to close the Strait of Hormuz. But while Iran might hope this would create pressure on Israel to end its strikes, they could just as easily draw the US and others in, as well as seeing Gulf States publicly support action.

For the UK, such an expansion would pose additional dilemmas. It has personnel at both US and UK facilities across the Middle East, and essentially no ballistic missile defences of its own

For the UK, such an expansion would pose additional dilemmas. It has personnel at both US and UK facilities across the Middle East, and essentially no ballistic missile defences of its own. It would therefore have to rely on US Patriot batteries, although UK Typhoon aircraft could intercept drones or cruise missiles. Meanwhile, the UK’s minehunters based in Bahrain might be called upon, but would need protection against Iranian fast boats or coastal defence missiles.

Operation Rising Lion has started with a series of unambiguous tactical successes. Israel is benefitting from a well-prepared plan, having built and acquired the capabilities to implement it at a time of vulnerability for the Islamic Republic. It is possible that it results in a weakened Iran, with a severely crippled nuclear programme or even a collapse in the regime, and its military execution might be studied for years to come. But such an outcome is by no means assured given the uncertain dynamics inside Iran and the possible interest of President Trump in returning to negotiations.

Netanyahu may be aiming at an ambition which can’t be achieved in the time available through military means. Therefore, it remains open as to whether it provides a definitive answer to the Iranian problem or represents a well-executed delaying action – one which exacerbates Iranian threat perceptions and drive for a nuclear deterrent.

© RUSI, 2025.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the authors', and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

For terms of use, see Website Terms and Conditions of Use.

Have an idea for a Commentary you'd like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we'll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. View full guidelines for contributors.

This commentary was amended on 19 June 2025 to improve accuracy.

WRITTEN BY

Darya Dolzikova

Senior Research Fellow

Proliferation and Nuclear Policy

Matthew Savill

Director of Military Sciences

Military Sciences

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org