The ‘Oil War’ between Iran and Saudi Arabia

Despite the relatively harmonious atmosphere at the last meeting of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in Vienna, the behind-the-scenes ‘oil war’ between Iran and Saudi Arabia continues.

The last OPEC meeting was characterised by a positive atmosphere and general optimism over the slight recovery of the oil market, after oil prices settled above $50 a barrel for the first time in seven months. According to Iran’s oil minister Bijan Namdar Zanganeh the meeting took place ‘without any tension’ adding that, after four years of quarrelling, Tehran and Riyadh had even agreed on a new UN Secretary-General. However, there was no agreement over oil production quotas intended to bolster or even increase oil prices, an indication that tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia over the management of the oil market remain high.

In February, as oil prices dropped to 30 dollars a barrel, Saudi Arabian officials met their counterparts from Russia, Venezuela and Qatar to discuss options for an oil production freeze to stabilise output levels. Nothing came of this, despite two months of negotiations. Worried that Iran could progressively increase its market share the kingdom refused to contemplate a freeze in output. In turn, Iran refused to accept production quotas which would have stopped it returning to pre-sanctions output levels, viewing the move as an attempt by the Kingdom to prevent it from resuming its pre-sanctions position in the market.

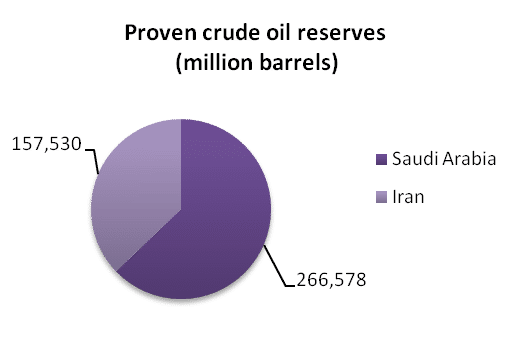

Following the implementation of the comprehensive nuclear agreement, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, in January this year, and the removal of sanctions from the country’s energy sector, Iran declared its intention to return to production and export levels that pre-dated the imposition of the EU oil embargo in March 2012. By doing so, it hoped to recapture markets that had been lost during the sanctions years. Had it accepted the idea of an oil freeze as proposed by the Saudis, Iran would have limited itself to producing one million barrels per day below its historic capacity, thereby foregoing market share to other producers, particularly Saudi Arabia. This seemed particularly unreasonable to the Iranian leadership, which saw the Saudis as primarily responsible for the fall in oil prices. In fact the kingdom has broader aims in allowing the price of oil to slide, including its battle against US shale outputs, but the Iranians nonetheless regarded the Saudi move as being primarily directed against them.

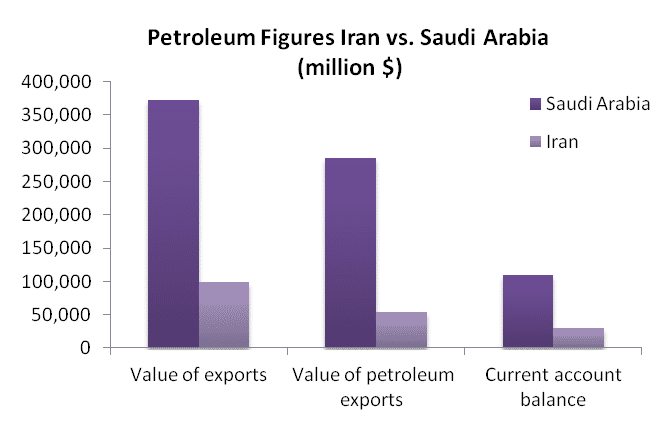

After dismissing the oil-freeze plan, Iran, thus proceeded with its intention of regaining its lost market share, and in April the country achieved production levels last reached in November 2011, pumping almost 3.6m barrels a day (b/d) and exporting 2m b/d of crude. However, precisely because of the global slump in oil prices, Iran is unlikely to enjoy the revenues it attracted for similar volumes before 2012. Aware of this, the administration of President Hassan Rouhani has focused on reducing the dependency of government revenue on oil exports – the mainstay of the Iranian economy since the 1970s – aiming instead at strengthening economic diversification, private sector growth, and exports in the non-oil sector.

A similar step has been undertaken by Saudi Arabia, which, on 25 April published its ‘Vision 2030’, an ambitious reform plan, aimed at addressing the kingdom’s addiction to oil revenues. The drop in global oil prices has, in fact, put the monarchy under strong financial pressure, leading to a record budget deficit of US$ 98 billion last year, and prompting Riyadh to raise US$ 10 billion-worth of borrowing on the international markets, for the first time in 25 years.

While both Iran and Saudi Arabia are thus focusing on reducing their dependency on oil, their rivalry in the energy sector is driving them to continue what the Iranian oil minister has defined as an ‘unwritten war’ between the two countries over oil productionand export.

At least for the moment, therefore, Tehran and Riyadh both prefer to resist an oil output cap, even at the cost of maintaining low oil prices and revenues. Saudi Arabia has taken additional steps to slow Iran’s efforts to increase its oil exports: in the past few weeks, it has banned carriers of Iranian crude from its waters and has cut its oil prices to European customers by 35 US cents a barrel, specifically targeting Iran’s prospective market. The kingdom has also considered further raising its oil production, flooding the market in order to weaken its main competitor. Iran, meanwhile, has been offering discounts to its customers in Asia, selling its oil at 60 cents below Middle East benchmark prices and aiming at undercutting Saudi Arabia.

This mounting competition between the two oil giants each attempting to use oil policy as a tool to gain political influence in the region is unlikely to end anytime soon: the outcome will largely depend on which country will be better equipped to withstand lower oil prices in the long run, while the unintended consequence will likely be a further destabilisation of the oil market.

WRITTEN BY

Dr Aniseh Bassiri Tabrizi

External Author