The EU in Chinese Media: Interpreting Xinhua's Reporting from 2012–2021

Reporting on the EU by China’s Xinhua News Agency has greatly increased over the past decade. What can analysis of the coverage tell us about Chinese attitudes to the EU?

The EU continues to refine its approach to a newly ambitious China that has been empowered by decades of strong economic growth. For Europe, China is simultaneously a 'cooperation partner' (on climate change), a ‘negotiating partner' (on trade), a ‘strategic competitor' (in economic terms) and a 'systemic rival' (having differing values and politics). How to strike the right balance between these different facets?

The answer depends in part on what conclusions are drawn about Chinese views and intentions. Any effort to interpret these views encounters the difficulty that public statements designed for foreign audiences may be influenced by Sun Tzu's dictum about confusing the enemy, so that they cannot fathom one's real intent. A further problem is an asymmetric language barrier. China is more familiar with the output of European media than Europe is with that of Chinese media.

In a recent briefing for the European Parliamentary Research Service, we analysed Chinese-language reporting on the EU by the Xinhua News Agency from 2012 to 2021. Xinhua, founded by Mao Zedong in 1931, is China's largest news agency. It is firmly under party control: its president, He Ping, is a member of the Communist Party's Central Committee.

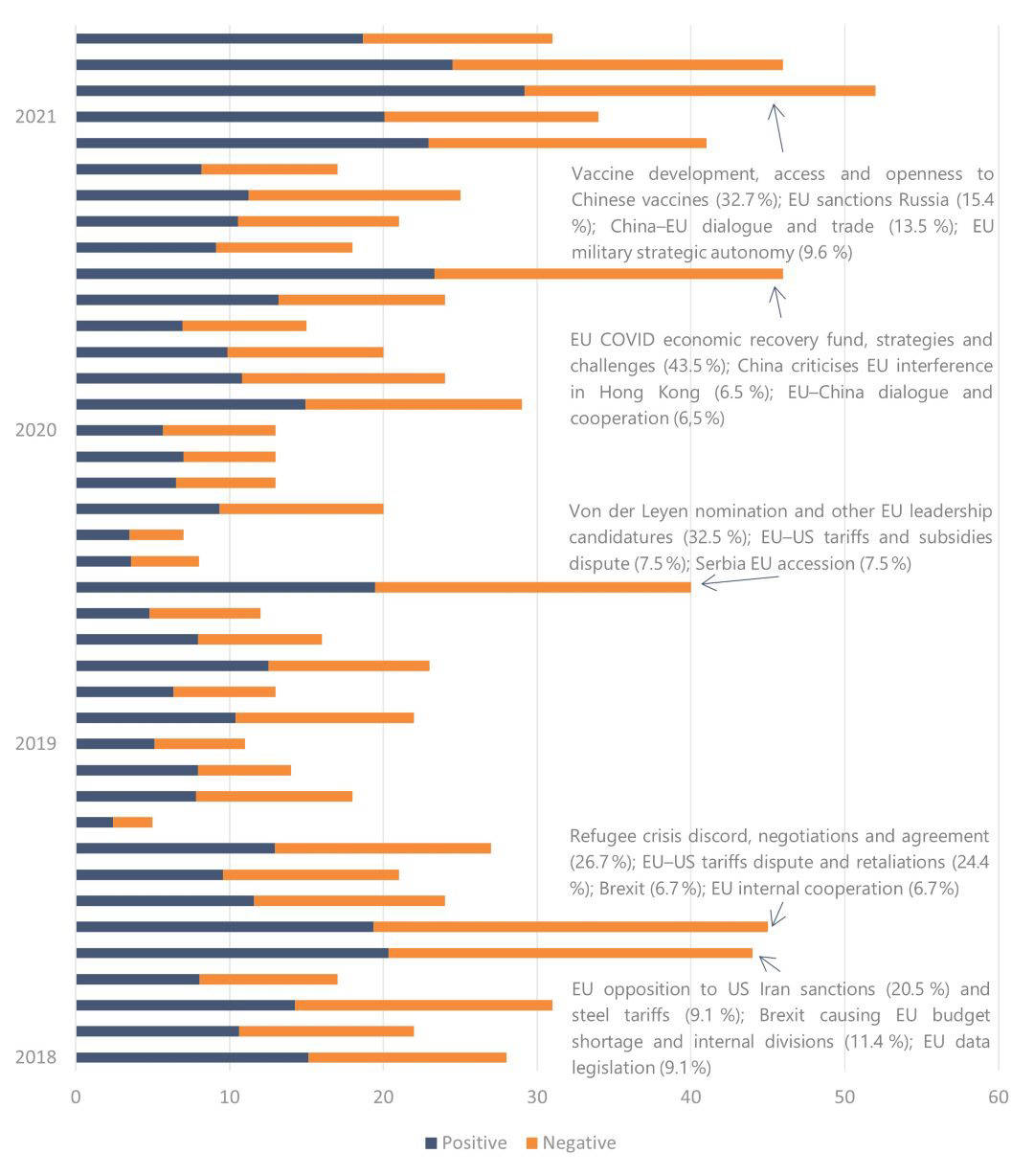

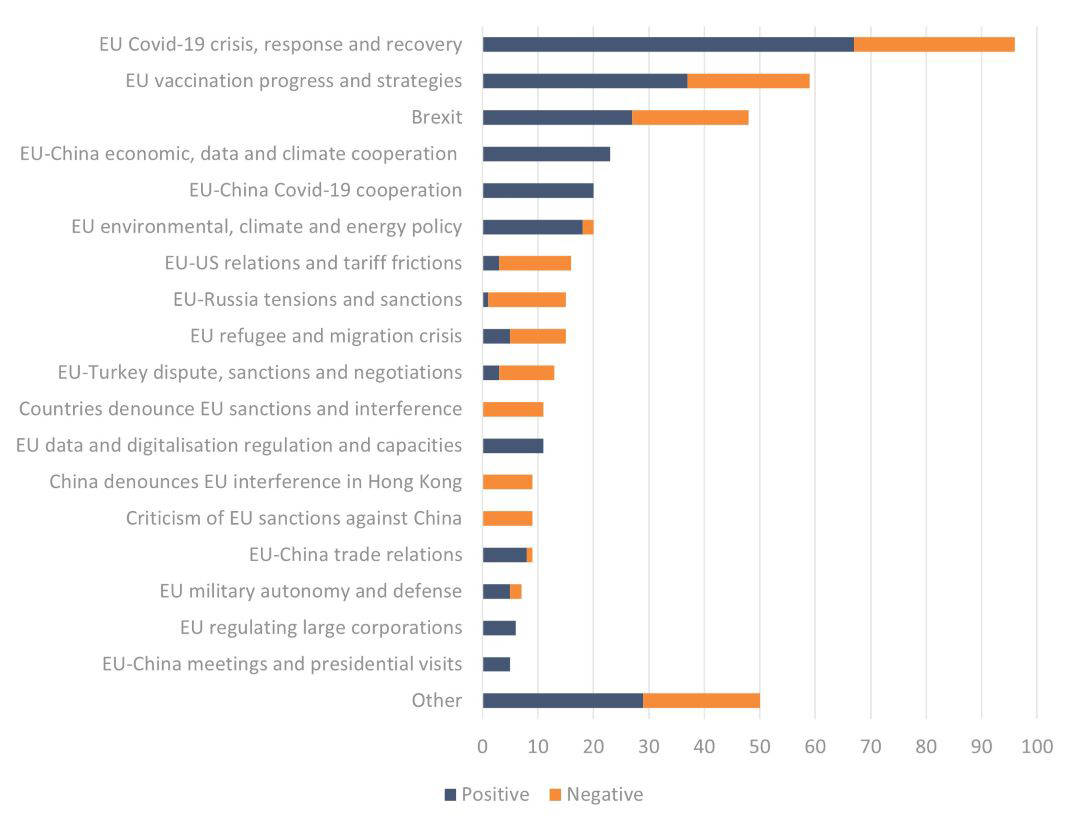

We identified and retrieved 1,158 Chinese-language articles from Xinhua's website with the Chinese term for the EU – '欧盟' – included in the title. We used text-mining software to extract main themes, month by month. We then applied automatic sentiment analysis to identify whether the tone of the coverage was positive or negative. We also manually reviewed 441 articles from 2020 and 2021 for a closer look at trends in coverage during the coronavirus pandemic.

Two structural trends emerged. First, Xinhua has greatly expanded its coverage on the EU over the past decade. This is associated with several visits to Europe by President Xi Jinping from 2018.

Second, the tone of the coverage is neutral, rather than negative. Automated sentiment analysis has its limits: for example, it struggles to gauge humour or irony. In this case, our findings are generally consistent with surveys within China of opinions about Europe. One could speculate that China prefers to reassure its citizens of positive relations with the EU, especially at a time of heightened international tensions in the wake of the pandemic.

As regards content, we identified three main trends. First, the coverage reflects continued Chinese interest in positive relations with the EU, and some measure of support for European integration. This extended to coverage of Brexit, and also characterised reportage on cooperation during the pandemic. Second, few details are given of EU criticism of China, which is invariably dismissed as unfounded. Third, disagreements between the EU and the US were reported prominently.

A Sunshine Policy?

Xinhua’s reports suggest continued Chinese interest in positive relations with the EU, and a degree of support for European integration. Coverage has been supportive of EU initiatives and regulations on data, climate and energy; it talks of the potential for EU–China cooperation in these fields, to supplement existing cooperation on trade and investment.

Xinhua coverage in the week following the UK's formal withdrawal was surprisingly supportive of the EU. It cited upbeat comments by French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel that Brexit would not halt EU integration, but would rather be an opportunity for deeper integration; Brexit was described as a potential catalyst for EU reform. Other articles focused on challenges, such as post-Brexit divisions over migration and budget contributions.

Xinhua's reporting reinforces the view that Beijing is favourable to the emergence of the EU as a balancing power in relations with the US

Xinhua has emphasised positive EU–China cooperation during the pandemic. A notable report in February 2020 followed a meeting between EU High Representative Josep Borrell and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi at the Munich Security Conference. This claimed that Borrell expressed appreciation of China's handling of the pandemic, and agreed that 'some countries' criticism stems from jealousy of China's development achievements'. No such statement can be retrieved from the conference website or EU sources mentioning the meeting. The report fits into a previously observed pattern of selective or unverifiable quotation of Europeans supposedly praising Chinese leadership.

Xinhua has been moderately positive on EU policies in response to the pandemic, including regarding vaccines. In March 2020, Xinhua described the pandemic as a ‘critical test for the EU coordination mechanism’, saying that 'if the EU does not effectively coordinate each country's response to the pandemic, this will undermine the European peoples' confidence in the EU and aggravate EU scepticism'. North-south divides during EU negotiations on the economic recovery fund were emphasised. In contrast, another Xinhua commentary speculates that the pandemic could likewise be an opportunity for EU integration.

Bones of Contention

Chinese and EU perspectives on matters of human rights and democracy differ greatly. Xinhua criticises EU complaints about Xinjiang and Hong Kong, and denounces sanctions against China. Yet the issue is to a certain extent downplayed. The serious row that flared over sanctions in March 2021 was covered in just seven of 46 articles about the EU that month, and most of these were a largely identical piece disseminated through multiple outlets.

Xinhua similarly condemns EU sanctions against countries like Russia and North Korea. This is consistent with the longstanding Chinese position that internal affairs are strictly a country’s own business. It may also reflect a strategic goal of reinforcing solidarity among those subject to criticism from the EU. Opposition to Western sanctions is clearly an area where China and Russia have common ground.

Divide and Rule?

Xinhua’s emphasis on EU cooperation with China stands in contrast to its coverage of EU divisions with the US. In the articles reviewed, the US is the second most mentioned country (after the UK). This shows that reporting of the EU is often framed in the broader global context.

The period of Donald Trump’s presidency provided plenty of scope for articles on EU–US disputes. This reinforces the view that Beijing is favourable to the emergence of the EU as a balancing power in relations with the US. China remains sceptical about the EU’s ability to achieve strategic autonomy, but articles about EU calls for increased military autonomy and defence capacity tend to emphasise opportunities rather than threats. This also reflects China’s stated preference for the EU to become a pole in a multipolar world order that is able to balance US power. In one scenario, the EU could leverage this Chinese interest to its own advantage, for example in trade negotiations.

Ultimately, the EU’s approach will depend more on how it sees China, rather than on how China sees the EU. Large-scale human rights abuses in Xinjiang and the suppression of democracy in Hong Kong are damaging China’s standing in Europe. They also feed into the perception that China is undergoing an authoritarian shift internally, and emerging externally as a systemic challenge to democratic governance.

This makes it all the more advisable to follow another dictum of Sun Tzu: that we should become acquainted with the designs of our neighbours, and always consider the favourable or unfavourable conditions of our counterparts.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the authors’, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.