Big Data and Policing: An Assessment of Law Enforcement Requirements, Expectations and Priorities

This paper explores the potential applications of big data technology to UK policing.

In recent years, big data technology has revolutionised many domains, including the retail, healthcare and transportation sectors. However, the use of big data technology for policing has so far been limited, particularly in the UK. This is despite the police collecting a vast amount of digital data on a daily basis.

There is a lack of research exploring the potential uses of big data analytics for UK policing. This paper is intended to contribute to this evidence base. Primary research in the form of interviews with 25 serving police officers and staff, as well as experts from the technology sector and academia, has provided new insights into the limitations of the police’s current use of data and the police’s priorities for expanding these capabilities.

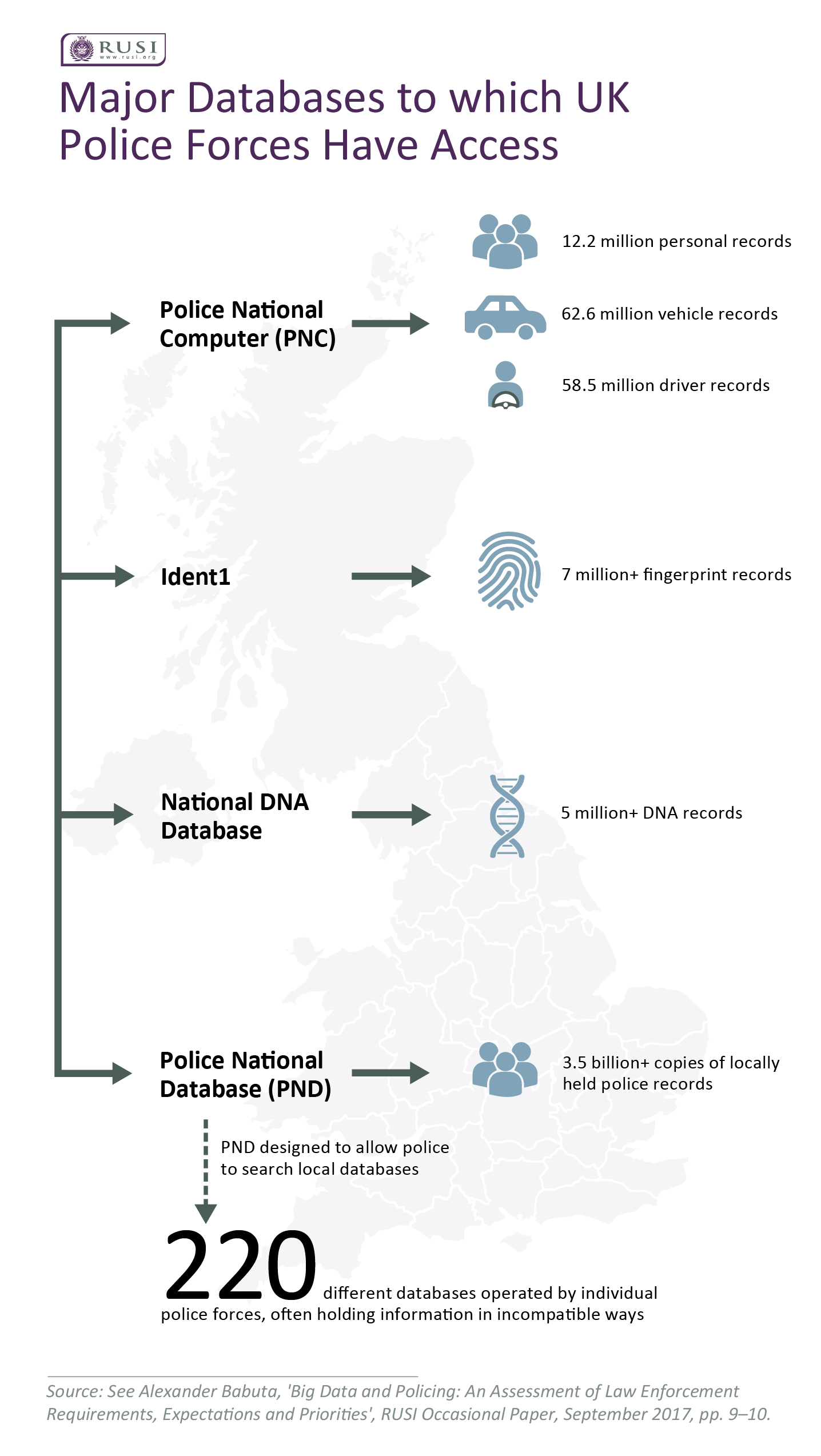

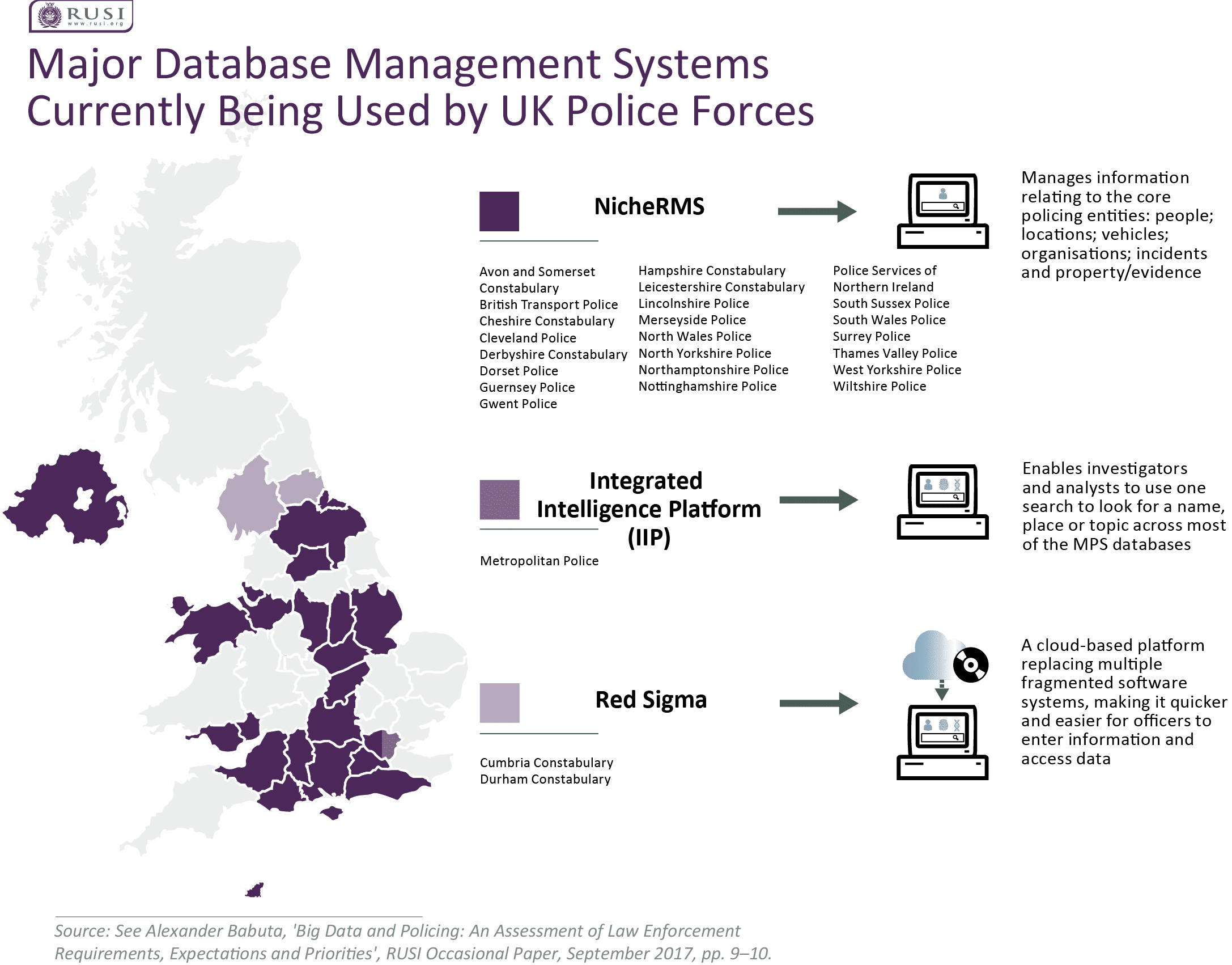

The research has identified a number of fundamental limitations in the police’s current use of data. In particular, this paper finds that the fragmentation of databases and software applications is a significant impediment to the efficiency of police forces, as police data is managed across multiple separate systems that are not mutually compatible. Moreover, in the majority of cases, the analysis of digital data is almost entirely manual, despite software being available to automate much of this process. In addition, police forces do not have access to advanced analytical tools to trawl and analyse unstructured data, such as images and video, and for this reason are unable to take full advantage of the UK’s wide-reaching surveillance capabilities.

Among the numerous ways in which big data technology could be applied to UK policing, four are identified as key priorities. First, predictive crime mapping could be used to identify areas where crime is most likely to occur, allowing limited resources to be targeted most efficiently. Second, predictive analytics could also be used to identify the risks associated with particular individuals. This includes identifying individuals who are at increased risk of reoffending, as well as those at risk of going missing or becoming the victims of crime. Third, advanced analytics could enable the police to harness the full potential of data collected through visual surveillance, such as CCTV images and automatic number plate recognition (ANPR) data. Fourth, big data technology could be applied to open-source data, such as that collected from social media, to gain a richer understanding of specific crime problems, which would ultimately inform the development of preventive policing strategies.

There are at present a number of practical and organisational barriers to implementing these technologies. Most significantly, the lack of coordinated development of technology across UK policing is highly problematic for big data, which relies on effective nationwide data sharing and collaboration. Financial cuts in recent years have also severely hindered technological development, as the majority of police IT budgets is spent supporting existing legacy systems, with little funding available to invest in new technology. Finally, there are significant legal and ethical constraints governing the police’s use of data, although these are not a main focus of this report.

These barriers are by no means insurmountable, and it is expected that, in the coming years, advances in the police’s use of technology will enable the successful development of big data policing tools. It is imperative that such development is informed according to specifically identified requirements and priorities, and this report identifies several areas of particular interest that warrant further investigation. Despite the budget cuts of the kind imposed since 2010, it is crucial to invest in new technology, as the costs of the initial investment will be more than recuperated by the efficiency savings made in the long term.

Recommendations

Police Forces, Police and Crime Commissioners

- Any major development in big data technology should be informed by direct consultation with a representative sample of operational police officers and staff.

This has several positive outcomes for both the developer and the end user. From a development perspective, technological investment will be directly targeted to address specific requirements, rather than being based on ad hoc and speculative research. From the police perspective, officer buy-in will be improved both at the front line and within management.

- UK police forces should prioritise exploring the potentials of predictive mapping software.

Predictive hotspot mapping has been shown time and again to be significantly more effective in predicting the location of future crimes than intelligence-led techniques. However, few forces have integrated the practice into current patrol strategies. The police collect a large amount of historic crime data that could be used to predict where crime is likely to occur, allowing limited resources to be directly targeted to where they are most needed.

- The digital aspects of any serious or long-term investigation should be managed by a digital media investigator, who takes responsibility for becoming the technical lead for specific operations.

Almost all police investigations have a significant digital component, but investigations are often conducted without a coherent digital strategy, with officers reporting a lack of coordination between teams working on different types of data. Digital media investigators, which most police forces are yet to fully utilise, can fill this void and represent a potentially highly valuable resource for digital investigations.

- Analytical tools that predict the risks associated with individuals should use national, rather than local data sets.

Predictive analytics makes it possible for police forces to use past offending history to identify individuals who are at increased risk of reoffending, as well as using partner agency data to identify individuals who are particularly vulnerable and in need of safeguarding. Analysis of this kind is currently carried out using local police datasets, but the use of national datasets is necessary to gain a full understanding of these risks.

Home Office, College of Policing and the Police ICT Company

- A national big data procurement strategy should be developed to coordinate technological investment across all UK police forces.

The highly localised structure of UK policing has resulted in wide variation in the levels of technological development between different police forces. Forces pursue technological change in isolation, with little coordination at the national level. The Home Office should issue clear national guidance for procurement of big data policing technology to ensure that future investment in this area is not wasted.

- A standardised glossary of common terminology should be developed for entering information into police databases.

When retrieving information from police databases, investigators are required to perform keyword searches, which involves guessing every potential synonym for a particular topic of interest. This makes it particularly difficult to collate and cross-reference information collected from different sources. A standardised lexicon would address this issue, while also enabling the development of useable text-mining software.

- Shared MASH (Multi-Agency Safeguarding Hub) databases should be created to allow for better data sharing between the police and partner agencies.

Local authorities, social services and the police should collaborate closely when identifying vulnerable individuals in need of safeguarding. Shared MASH databases would facilitate this while also giving the police quick access to information that could prove vital for ongoing investigations. At present, data-sharing deficiencies mean that the police’s understanding of vulnerability is somewhat one-dimensional.

- A clear decision-making framework should be developed at the national level to ensure the ethical use of big data technology in policing.

There is currently no clear decision-making framework governing the ethical use of big data technology by public sector organisations in the UK. This must be addressed as a matter of urgency, to ensure that organisations such as the police are able to make effective use of these new capabilities without fear of violating citizens’ right to privacy.

Software Developers

- Provision of new analytical software should be accompanied by an officer training session and/or instructional video delivered by the software developer.

Analytical tools are only as effective as the individual operating them, and investment will be wasted if officers are unable to effectively use the new technology. As modern software solutions are highly intuitive and can typically be adopted with ease, training in this context could be provided in the form of a brief presentation or an instructional video that officers can refer to at their convenience, demonstrating how a new piece of technology works and why it is effective.

- All data applications should include an event log feature that is permanently enabled, documenting any changes that are made to a data set.

When presented with a new dataset, analysts should be able to view a corresponding event log, documenting how and when the data has been modified, and by whom. This will ensure continuity and prevent duplication from one user to the next.

- Developers of predictive policing software should conduct further research into the use of network-based models for generating street segment-based crime predictions.

Recent research suggests that a calibrated network-based model which generates street-segment predictions delivers a significantly higher level of predictive accuracy than traditional grid-based predictions. Street-segment predictions are more useful for policing purposes than arbitrary grids, and these preliminary findings suggest that further research is needed to refine such models and integrate them within existing predictive policing software.

Further Research

- Further research is needed to explore the potential uses of Risk Terrain Modelling (RTM) for identifying areas most at risk of experiencing crime.

Current predictive mapping methods rely on past criminal events alone to predict future crimes, and are indifferent to the underlying geographical and environmental factors that make certain locations more vulnerable to crime. RTM takes account of these underlying environmental factors to provide a comprehensive analysis of spatial risk, and some studies have shown that RTM has better predictive power than retrospective hotspot mapping.

- Further research is needed to explore the use of harm matrices to assess the harms caused by different types of crime.

At present, in most forces, the prioritisation of police resources is based primarily on the total volume of crime in a given area, as opposed to the harms caused by different types of crime. Tools such as the MoRiLE Matrix demonstrate that it is possible to use data to understand harm in a much deeper way, by taking into account factors such as the harms caused to individuals, communities and the economy. Further research is needed to explore these potentials in greater detail, and develop more sophisticated analytical methods for evaluating the harm caused by different types of crime.

- Further research is needed to explore the police’s potential uses of big data collected from the Internet of Things.

It is likely that in the coming years there will be a significant increase in the amount of data being transmitted from sensors in the urban environment. While such data can be used to enhance the performance and efficiency of urban services, such as transportation networks, hospitals and schools, it could also transform the way urban environments are policed.