Trump’s Foreign Policy After Year One: A Look Back, A Look Ahead

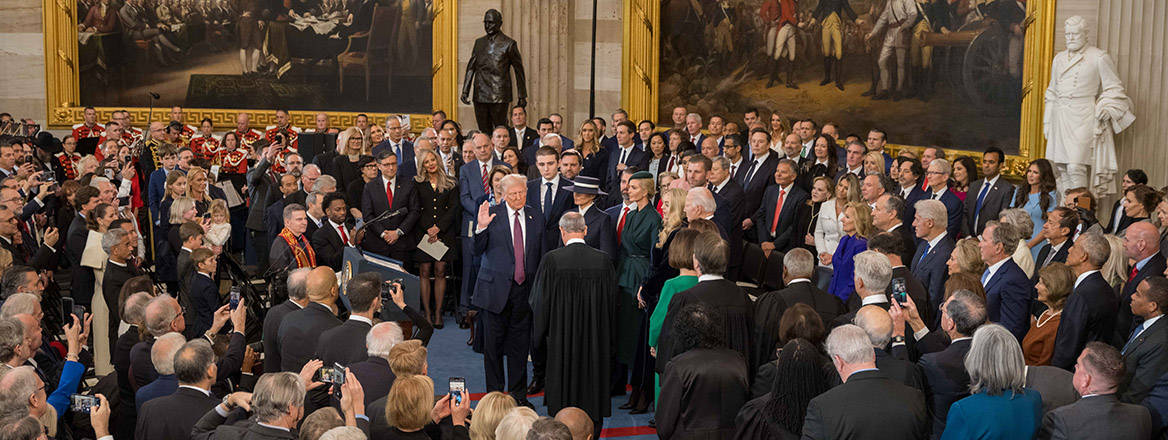

Within 12 months, the US President’s second term in office has had an impact on international relations unlike any in recent memory.

Unpredictable. Unorthodox. Unprincipled. Foreign leaders, military officers, think tank experts, academics and prominent journalists have used these and far harsher words to criticise the Trump administration’s foreign policy during this past year.

The main reason for this assessment, and what has most unnerved America’s friends and allies around the world, is the Trump administration’s enthusiastic disruption of the existing liberal international order. Previous American administrations, from both parties, constructed this order by embedding US power within international alliances, institutions, rules and norms, seeking to coordinate with like-minded states and build the widest possible consensus on key issues, while prioritising long-term stability. For all its shortcomings, this order is credited with helping win the Cold War, lift millions out of poverty, spread democracy, alleviate famine and manage great power conflict.

Within a remarkably short period, the Trump administration has taken a sledgehammer to this old order, redefined America’s interests, and reframed its relationships with long-standing friends and great power adversaries. It is accelerating the old order’s demise and ushering in a new one with a very different set of behaviours and no rules. This shift has upset all those countries, most of all, those in Europe, that have come to depend on the US for its security assurances and guarantees, commitment to free trade and devotion to a rules-based international order.

Trump 2.0 has instead emphasised transactional deals, looking to maximise short-term gains, often economic in nature. It has sought to leverage the military, diplomatic and economic power the US has accumulated over decades to coerce or compel countries to do its bidding. The President has raged against a corrupt international trading system that ‘screwed’ the US, and claimed executive authority to unilaterally levy tariffs on offending countries. His administration extended US power to the Western Hemisphere, which included abducting Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and claiming the country’s oil, unilaterally renaming the Gulf of Mexico as the Gulf of America and reaffirming American control over the Panama Canal. It has downplayed democracy promotion and human rights; it has withdrawn from multilateral institutions. This is the real divide between the Trump administration and its predecessors: the ends to which Washington now deploys America’s military, economic, cultural and diplomatic power.

This critical assessment also derives from the surprise, even shock, at how dramatically and swiftly the second Trump administration has deviated in its personnel, rhetoric and behaviour from its first term.

Instead of appointing experienced Washington, DC veterans to major national security positions, this time around Trump selected staff on the basis of their MAGA credentials, their personal loyalty and how telegenic they appear. The search for suspected members of the ‘deep state’ led to the firings, removals, or forced retirements of scores of experienced intelligence and State Department officers, including the recall of two dozen ambassadors at year’s end. The public got a sense of his national security team’s unseriousness when their March 2025 discussions over bombing the Houthis were disclosed in an unclassified Signal group chat. At times, the President conducted foreign policy without input from other countries – even those existentially invested like Ukraine or NATO members. And repeatedly during the year, the President would cavalierly announce a new foreign policy or contradict existing policy, often revealed to the world (and his own administration) through his social media platform, Truth Social.

Trump sees Russia and even China more as potential investment opportunities and trading partners, not as authoritarian regimes who repress their own people and threaten their neighbours

Identifying an overriding theme to characterise the Trump administration’s foreign policy is challenging, given the contradictions between its America First isolationism and diplomatic and military interventions overseas, between its belligerent jingoism and deep-seated grievances. The National Security Strategy issued in December 2025 reflected the contradictions within the administration and failed to outline a coherent strategy. As the President said last June, he alone decides what America First means.

Still, there appear to be two reappearing themes: a real estate mogul’s preference for deal-making with a commercial upside and a ‘might makes right’ mentality that allows the President to speak and act impulsively with few checks and balances. Termed ‘transactional nationalism’, Trump privileges commercial advantage, views military conflict as economically ruinous and contrary to a state’s larger self-interest and yet is unafraid of the limited application of US military force.

So while it is easy to award failing marks to Trump’s foreign policy when measured against the more traditional, internationalist ones of his predecessors, it is a different – and arguably fairer – exercise to assess the President’s foreign policy on its own terms. After one year, has Trump’s foreign policy approach made the US more safe and secure today?

Great Power Rivals No More?

A prime responsibility of every American president is to manage relations with other great powers. Trump has reframed the competition with China and fundamentally reset relations with Russia. He sees Russia and even China more as potential investment opportunities and trading partners, not as authoritarian regimes who repress their own people and threaten their neighbours. Indeed, the National Security Strategy did not call either Russia or China authoritarian and downplayed universal values of human rights and democracy promotion more generally.

In 2025, the US conducted its economic competition with China within a national security lens. The US sought to secure its global technology supply chains to reduce its dependence while also weakening China’s military capabilities. This led to US export restrictions on advanced semiconductors; China retaliated by withholding rare earth minerals.

In April the President raised duties on Chinese goods, China retaliated and Washington and Beijing then escalated tariffs to 145% and 125%, respectively. Cooler heads eventually prevailed, tariffs were reduced and disagreements kicked into the new year, but not before the US relented and agreed to sell China advanced semiconductors. Neither side tipped the world into recession and neither side confronted each other militarily over Taiwan (even though Congress passed an $11 billion military sales package to Taiwan), which was something to celebrate. Trump and Xi Jinping are scheduled to meet four times in 2026.

Relations with Russia were far more deferential than most Americans supported, as the President leaned into his personal relationship with Vladimir Putin, often praising him, excusing Russia’s desire to subordinate Ukraine, publicly dressing down President Volodymyr Zelenskyy (‘You don’t have the cards!’) and dismissing Ukraine’s legitimate security concerns. Trump also did not comment on Russia’s repeated hybrid attacks (including drones, the slicing of underwater cables and cyber warfare) against NATO members. Instead, the President talked up the investment opportunities and economic potential of a peaceful Russia able to trade again with the US, Europe and the world.

Yet for all his fascination with Putin, Trump agreed to send billions of dollars of new and advanced weapons to Ukraine, to be paid for by the Europeans. He continued US intelligence sharing (aside from a brief pause in March). And he sustained his administration’s efforts to end the war.

More than either Russia or China, Europe was the target of much of the Trump administration’s ire in 2025. Starting with the fusillade unleashed by Vice President J.D. Vance at the Munich Security Conference in February 2025 and bookended by the rhetorical attacks on Europe in the National Security Strategy released in December, the Trump administration made clear its view that Europe has been free riding on America’s security umbrella, overregulating its economies and stifling innovation, taking advantage of the US through unfair trade practices, selectively targeting far-right populist parties, compromising its commitment to free speech and democratic principles and allowing the prospect of ‘civilisational erasure’ through a porous border policy that brings millions of people to Europe who do not share its culture and are not assimilated into their societies.

The administration’s confrontational approach and its conditional support for European security troubled European leaders who preferred to continue funding generous social welfare and retirement programmes rather than ramping up their military preparedness and battlefield readiness. After more than a half century of requests from American presidents of both parties, at the June NATO summit in the Hague, the Allies succumbed to Trump’s pressure and pledged to increase their defence spending significantly, to 5% of their GDP.

While the assumption of more responsibility by Europe for its own defence promises to make NATO more secure in the long term, it created real problems in the short term. Europe has struggled to appropriate more funding for defence, conscript more soldiers, develop its industrial base and telescope the defence procurement cycle. Intending to accelerate European efforts, the Pentagon announced in December that it wanted Europe to take lead responsibility for conventional warfare, including intelligence and missiles, by 2027. No one believes this timetable is feasible.

The worst case is that the administration assumes an even more isolationist approach to the world, retreating further from the global security role it has assumed since the end of the Second World War; and that when it acts militarily, it does so without consulting allies or adhering to international law

Nor were NATO allies exempt from the President’s efforts to create a trading system that favoured the US. He leveraged US threats to impose a baseline 15% tariff on most European exports to the US in return for duty-free status for most American exports to Europe. He insulted Canada by talking about making it the ‘51st state’. He ended 2025 as he started, casting a covetous eye towards acquiring Greenland, which actually belongs to a NATO ally. The President dramatically slashed USAID’s support for humanitarian and developmental assistance overseas and rejected the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. The National Security Strategy confirmed what should have been apparent much sooner: the US and Europe no longer share the same interests or the same values.

The Year Ahead: Scenarios

What can we expect from the Trump administration in year two? The President does not start from a position of domestic strength. He finished 2025 with a 36 percent approval rating, the lowest of any president at the end of his first year in the past half century. With the mid-term congressional elections looming and the historical likelihood of the minority party, the Democrats, retaking the House and, with it, control of the budget, committee agendas and subpoena powers, this is likely to be the President’s last year with maximum freedom of action in foreign policy.

The worst case is that the administration assumes an even more isolationist approach to the world, retreating further from the global security role it has assumed since the end of the Second World War; and that when it acts militarily, it does so without consulting allies or adhering to international law. It does not mismanage the strategic competitions with Russia and China so much as it neglects them. Russia continues to wage war against Ukraine, conduct ‘hybrid warfare’ against Europe, repress its own people and intimidate its neighbours. Citing America First, Trump refuses to sell US arms to Kyiv (although allowing Europe to do so) and suspends all intelligence sharing. Questioning the glacial pace of NATO members’ commitment to the 5% defence spending goal, Trump withdraws four US brigades from bases in Europe.

The US also reduces its presence in the Indo-Pacific region, giving China the green light to continue increasing its conventional forces and nuclear arsenal. China conducts live-fire drills each quarter that impinge on Taiwan’s sovereignty and aggressively asserts its ‘historic right’ to the Nine-Dash Line portion of the South China Sea.

Despite the transformation of the Middle East last year with the end of the Assad regime in Syria, the weakening of Hezbollah in Lebanon, the devastation of Hamas in Gaza and the humiliation of the Islamic Republic of Iran, the Trump administration struggles to connect ends with means. With a weakened diplomatic corps and a fleeting White House attention span, it cannot capitalise on tactical successes and sustain diplomatic initiatives to institutionalise new governance structures for the ‘day after’ conflicts end.

America’s friends and allies around the world are forced to decide whether to reflexively acquiesce to America’s preferences, rapidly spend more money on defence in a quest for greater ‘strategic autonomy’, or hedge their bets by accommodating Moscow or Beijing. In a world with collapsing collective defence structures, some states openly debate whether they should develop an independent nuclear deterrent.

The best case is that the administration continues to engage the world, if only on a transactional basis

With little US leadership and less US funding, multinational efforts to address climate change, poverty, refugees and infectious diseases all continue to suffer. American soft power retreats against the disinformation campaigns from authoritarian regimes and the effective elimination of Voice of America, Radio Free Asia, Radio Farda and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. The draconian behaviour of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) against foreign nationals living and working in the US does further damage. International polls show that admiration and respect for America are at record lows.

The best case is that the administration continues to engage the world, if only on a transactional basis. It manages the strategic competitions with Russia and China sufficiently to avoid any incidents that escalate into open conflict. Trump somehow convinces Putin to end the war in Ukraine in a manner that preserves Ukraine’s sovereignty and safeguards European security. China and the US reduce tariffs to earlier levels, rebalance their trade and slowly continue to decouple their economies. They manage to avoid pushing the world into recession.

The $11 billion arms package to Taipei sent a strong signal to China that the US remains committed to Taiwan’s independence and will stand by its friends who are willing to defend their own interests. Beijing’s verbal and military provocations towards Taipei decline in number and intensity.

NATO members start to fulfil their defence pledges, reinvigorate their defence industrial base, expand their standing armies and provide their militaries with proper training and first-class equipment. Europe also develops new “mini-lateral” structures among groupings of the more powerful states (e.g., the UK, France and Germany) to expedite and coordinate decision-making on foreign and military matters.

Trump’s bold military mission to capture Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and bring him to justice in the US allows Venezuela’s economy to slowly rebound as its oil fields increase output. The regime releases political prisoners and by year’s end Venezuela holds and honours, fair and free elections.

Trump’s 20-point peace plan for Gaza’s renovation finally gets underway, offering a future without Hamas and new hope for its residents. A de facto alliance of Saudi Arabia, Israel and the Gulf states help stabilise Lebanon and Syria and minimise Iran’s regional malfeasance. There is revived talk of Saudi Arabia joining the Abraham Accords and extending diplomatic recognition to Israel.

Trump is again nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Conclusion

Amid all the questions and uncertainty over the Trump administration's strategy and principles, it is clear that under President Trump the US has changed irrevocably from the linchpin of the liberal world order where might did not automatically make right, where notions of state sovereignty and international law held purchase and where states largely operated within a rules-based world order defended and promoted by the US.

Historians will remind us that we are not in entirely new territory. Last century, world leaders and international institutions were inadequate to meet the challenges posed by lawless actors and reckless behaviour. The strongest countries declared spheres of interest and preyed upon weak states. The result was two cataclysmic global wars. We are not there yet, and may never be. But it feels like we moved a little closer over the past twelve months.

© RUSI, 2026.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

For terms of use, see Website Terms and Conditions of Use.

Have an idea for a Commentary you'd like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we'll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. View full guidelines for contributors.

WRITTEN BY

Ambassador Mitchell Reiss

RUSI Distinguished Fellow, RUSI International

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org