Export Controls Accelerate China’s Quantum Supply Chain

When export controls are seen as a tool to limit competitors’ technology advancements, they can have unintended consequences. Such is the case for quantum technologies, where export controls accelerate a localized quantum supply chain in China.

The development of quantum technologies is anticipated to bring both foundational capability advances to commercial and dual-use applications, including to computing, sensing, and the transfer of information. This makes quantum technologies a global political priority, including in the UK and the EU. Under the Biden administration, US leadership in quantum and other ‘force-multiplying’ technologies, such as advanced semiconductors, have become a key national security imperative.

The US has therefore intensified its export controls on quantum technologies aimed at China over the past year. These measures have resulted in disruptions to China’s quantum hardware and talent development, but they also accelerated China’s domestic quantum supply chain. By forcing leading laboratories and quantum start-ups to rapidly iterate with domestic suppliers in replacing foreign dependencies, export controls brought the demand side on board with Chinese localisation efforts.

On the supply side, the basis for a self-reliant Chinese quantum supply chain was created years ago by strong government support and indications of US quantum controls as early as 2018. Now, with a parallel quantum ecosystem rapidly emerging, it is only a matter of time until exports from Chinese suppliers arrive in Europe. This presents both risks and opportunities.

Escalating quantum controls in 2024

Although the US Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) initiated a ‘Review of Controls for Certain Emerging Technologies’, including quantum in 2018 already, list-based US export controls on quantum computing were only finalised five years later.

In the meantime, the US mostly relied on end-user controls, placing Chinese companies, institutes and universities on its Entity List for their involvement in quantum technologies. Absent licenses (which are usually denied), this bars affected entities from importing nearly any US-origin items. The most significant additions came in 2024, when the US also finalized outbound investment controls, banning most US investments in China’s quantum sector.

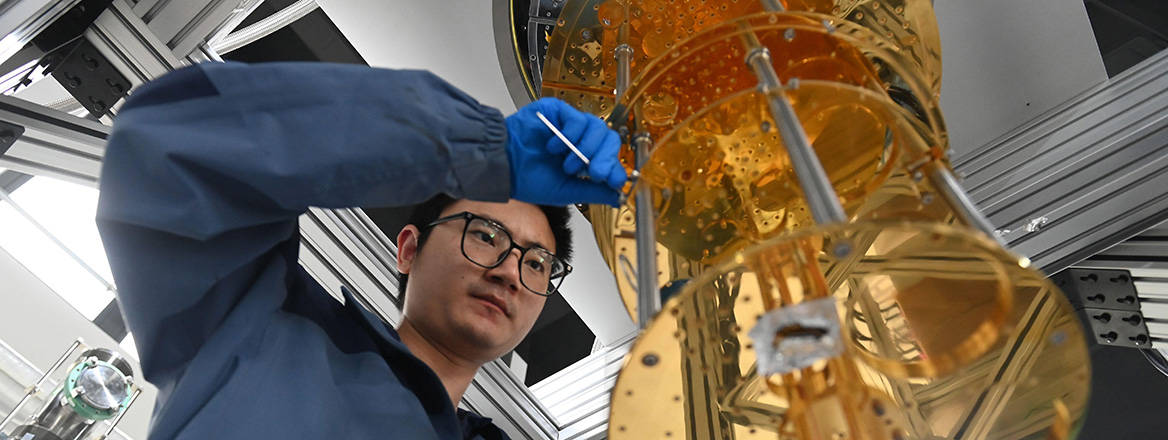

Escalating measures further, the BIS issued broad list-based quantum computing controls in September 2024 Besides requiring licenses for the export of (sufficiently powerful) quantum computers, the export of key components and related software is also restricted. For example, exporting dilution refrigerators to a Chinese research group or cryogenic circuits to a Chinese supplier of quantum computing systems would require license applications, with review policy ‘presumption of denial.’

China’s national security whitepaper acknowledges quantum technologies as a ‘double-edged sword’ but insists that cooperation and win-win results are unstoppable

The September 2024 controls are internationally coordinated and introduce an exception for partnering countries that enact similar controls on quantum technologies. The UK is currently listed among all US exceptions and, alongside other European countries, Japan, and Canada, has already introduced similar controls in the months prior to US controls.

The plurilateral alignment of the controls among an ad-hoc group of US partners is crucial to ensure that they are effective and limit self-harm. At the same time, closely tracking US controls limits the UK in independently setting rules.

Export Controls are Accelerating China’s Quantum Supply Chain

While export controls temporarily slow down Chinese quantum progress, they also turbocharge the development of a domestic supply chain and, in the long term, may run counter to the stated goal of maintaining technological competitiveness.

The long delay leading up to the current quantum export controls has given Chinese planners and entrepreneurs time to prepare. Compared to the deep and highly specialised semiconductor supply chain, the quantum supply chain is still more shallow and dispersed, making it more feasible to innovate around restrictions.

Before the restrictions, convincing buyers to choose unproven, local suppliers over established international alternatives was a key hurdle for Chinese upstream suppliers. Export controls limited the extent to which international companies could sell into China, forcing downstream labs and companies in China to turn to local alternatives and do their best to help them succeed.

Even where foreign options still exist, local suppliers often outperform foreign ones at service, especially on-premises repairs and support – something that would otherwise require a shipment to Europe or the US. Export controls exacerbate this competitive disadvantage by complicating customs procedures and adding uncertainty to the availability of cross-border support.

China’s commercial quantum ecosystem is frequently belittled: Chinese big tech largely left the sector, and state laboratories dominate the most impressive announcements. Nonetheless, comparing the competition in quantum to a ‘struggle between private free enterprise and state-directed communism’ fails to recognize Chinese efforts to create a thriving commercial quantum ecosystem.

An example of expanding commercial activity, China’s Quantum Internet Industry Alliance was established in 2022 and has since grown to over 90 members. In China’s leading university for quantum science, the market-driven commercialisation of research results is explicitly encouraged, with many resulting quantum start-ups. This system – including shared benefits for both the university and researchers to incentivize commercial application – is not dissimilar to Western universities, including in the UK.

More venture capital for quantum start-ups, admittedly dominated by government funds, is also a recent political priority.

Self-reliant supply chains for microwave interconnects and dilution refrigerators are less flashy than quantum supremacy claims, but they are part of the rapidly advancing foundation for China’s future quantum industry, accelerated by recent export controls.

Contrary to Western Perceptions, China is Still Keen to Internationalise its Quantum Sector

China’s quantum strategy is often framed as intentionally insular in Western media. While a push towards self-reliance is indeed central in China’s science and technology planning, relative to the US and the UK, China’s quantum sector is currently less securitised.

Leading Chinese quantum researchers call for international collaboration, foreign involvement in China’s quantum industry is officially encouraged, and China’s own quantum export controls are mostly limited to licenses for quantum cryptography and cryogenic components. In a recent call with German Chancellor Friedrich Merz, Xi Jinping highlighted quantum for the cultivation of ‘incremental cooperation.’

Official Chinese proclamations of benign open innovation do deserve scepticism due to stated ambitions of self-reliant technological dominance in key sectors. However, these same ambitions rely on participation in global standards, high-tech exports, and access to global IP, making an insular quantum strategy an unlikely proposition.

Many Chinese policy documents frame quantum technologies as a ‘future industry’, contrasted to a US approach that highlights quantum as a ‘national security imperative’ with a more narrow focus on leading capabilities. This resembles the situation in AI, where US policymakers see an arms race to super intelligence while Xi Jinping emphasises broad applications and (open source) ecosystem building.

China’s national security whitepaper acknowledges quantum technologies as a ‘double-edged sword’ but insists that cooperation and win-win results are unstoppable. With ‘non-development’ framed as the biggest security risk, more scientific and technological Chinese exports bolster China’s national security by proving the competitiveness of local champions, shaping global standards, and boosting economic development. In this view, quantum is just one piece in China’s broader strategy to move up the value chain.

At the current stage, it is therefore likely that Chinese quantum export restrictions remain largely limited to dual-use applications, as opposed to more comprehensive sectoral controls in the West.

Brutal domestic competition will create export pressure in China’s quantum supply chain, exacerbated by local government competition and many new entrants following the call to develop ‘future industries’ and hoping to fill the void left by foreign supplies.

It is unlikely that the Western quantum ecosystem will out-innovate an increasingly decoupled Chinese quantum sector across the board

While one should not expect Chinese quantum computers in European HPC centres anytime soon, the upstream supply chain in photonics, electronics, cryogenics and vacuum systems is bound to see Chinese entrants. Take the example of Precilaser, whose laser sources are used in quantum experiments. Besides taking domestic market share, Precilaser has exported nearly one hundred sets to Harvard University.

Currently, this export market is still in its infancy, with little international patenting for example. This gives policymakers in the UK time to consider both the risks and opportunities from the participation of Chinese quantum companies.

The UK's Handling of the Coming Chinese Quantum Exports

Unlike dependencies in end-devices such as 5G infrastructure, Chinese components in quantum R&D pose few direct security risks. Still, due to the importance of quantum technology to future economic security and the recent emphasis on technological sovereignty, the UK should monitor dependencies on Chinese suppliers and decide what it deems and does not deem acceptable. This is especially true for military procurement, which aims to expand links with deep tech and agile start-ups, including in quantum, among the reorganizations called for by the UK’s recent Strategic Defence Review.

However, if policy makers look beyond the defence tech angle, they will see that preventively closing the door to Chinese exports or introducing costly screening procedures risks doing more harm than good.

The development of quantum technologies is a long game, with some of the most significant foundational applications likely still more than 10 years in the future. It is unlikely that the Western quantum ecosystem will out-innovate an increasingly decoupled Chinese quantum sector across the board. Retaining channels through which innovations and new technological paradigms can diffuse to the UK is the prudent choice. This is often overlooked in the current emphasis on protecting Western innovations through export controls, implicitly assuming enduring and comprehensive Western leadership.

Besides export controls, import controls and government screening of business transactions will become more important as quantum technologies are adopted in the wider economy. The US already does the former, and the UK explicitly lists quantum technologies in its ‘National Security and Investment Act.’ These tools should be applied with caution. Joint projects, such as a reported quantum computing centre by China-based Origin Quantum in Spain, could create valuable pathways for diffusion and insight.

Too often, the quantum competition is seen purely through a national security lens, with policy tools chosen accordingly. Yet the reason that companies, and the Chinese government, invest billions in quantum technologies is firstly quantum’s potential as a future industry. This is no zero-sum competition, and as the sector matures, the UK should consider borrowing from China’s own past toolbox on technology transfer and local partnerships.

Access to China’s quantum supply chain, if established gradually, can contribute to a competitive UK quantum ecosystem, with companies able to build with the best there is in every category.

© Elias Huber, 2025, published by RUSI with permission of the author.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

For terms of use, see Website Terms and Conditions of Use.

Have an idea for a Commentary you'd like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we'll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. View full guidelines for contributors.

WRITTEN BY

Elias Huber

Guest Contributor

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org