The 40 'Red Hackers' Who Shaped China’s Cyber Ecosystem

Over two decades, China's informal hacker collectives morphed into key architects of China's cyber apparatus.

Between January and March 2025, the United States indicted or sanctioned individuals and companies linked to Chinese state-sponsored threat actors known as APT27, Red Hotel, and Flax Typhoon – labels used by cybersecurity researchers to group entities with similar tactics. Many of the individuals behind these groups trace their roots to an earlier community of elite hackers known as ‘red hackers’ or ‘Honkers’, active in online forums during the mid-1990s and 2000s.

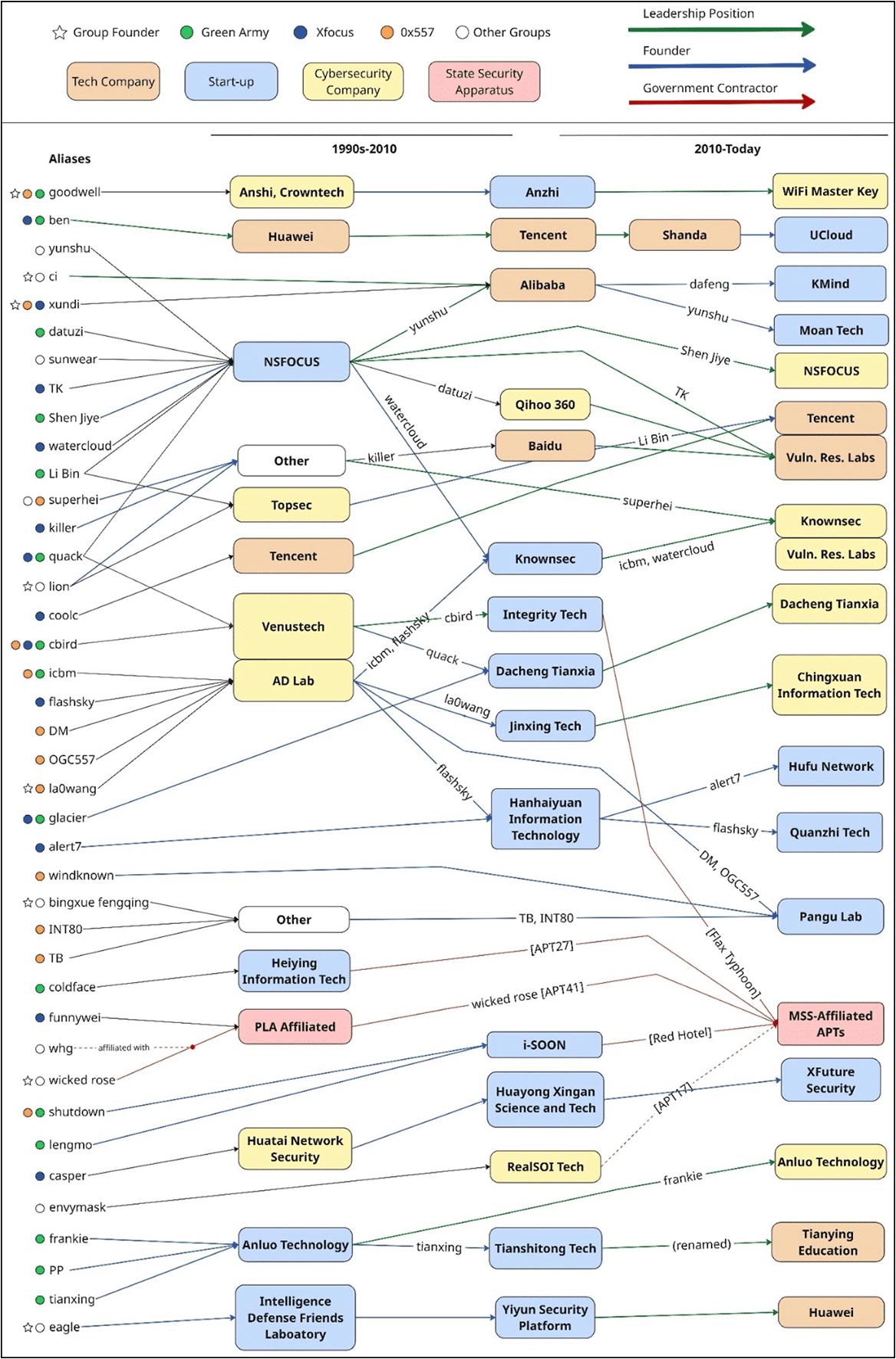

Over the following two decades, these Honkers evolved from informal hacker collectives into key architects of China’s cyber apparatus. Many founded security startups, helped build cybersecurity teams at major tech firms such as Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, and Huawei and helped shape a cybersecurity market driven by attack-defence capabilities. Today, these capabilities likely serve as key enablers of China’s advanced persistent threat (APT) groups, as cyber operations are increasingly carried out through private-sector proxies.

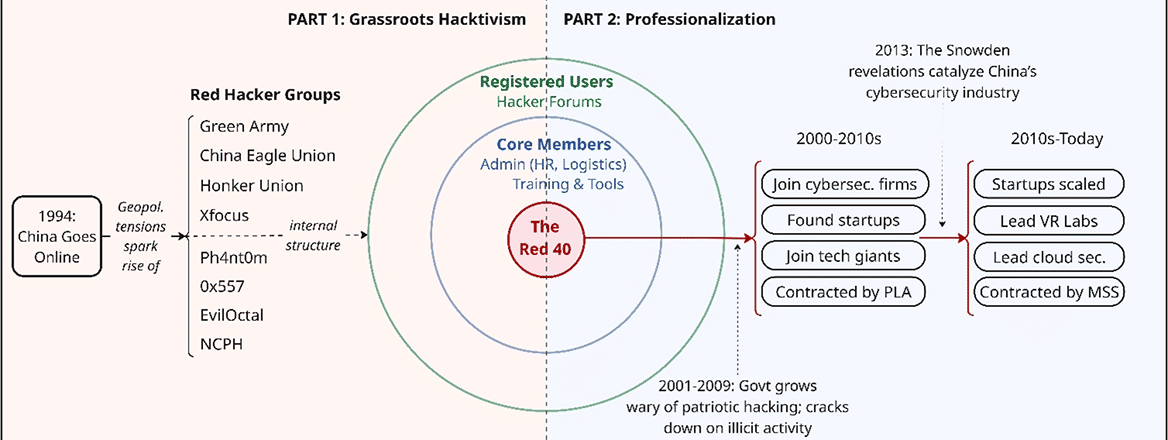

A recent report by the Cyber Defense Project at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich titled ‘Before Vegas: The “Red Hackers” Who Shaped China’s Cyber Ecosystem,’ charts this evolution. It focuses on 40 influential figures – referred to as ‘The Red 40’ – and traces how informal talent was gradually absorbed into a tightly integrated ecosystem: one where informal networks, private enterprise, and state interests intersect through a mix of grassroots experimentation, strategic alignment, and increasing institutional control.

The Making of the Red 40

The Red 40 came of age during China’s early internet era. After China connected to the global internet in 1994, universities became key hubs for connectivity and experimentation, helping foster hacker culture before widespread internet access. By the late 1990s, red hacker groups began to emerge, driven by nationalism, technical curiosity, and rising geopolitical tensions. Groups like the Honker Union, Green Army, and China Eagle Union gained prominence during a wave of ‘cyber wars’ between 1998 and 2001 – targeting foreign entities perceived as hostile to China, including the US, Taiwan and Japan.

These operations were both offensive and defensive, offering hands-on experience in real-world conditions at a time when China’s cybersecurity ecosystem was still in its infancy and formal training pathways were limited. Universities offered few dedicated programs, and mechanisms like Capture the Flag competitions(competitions are simulated cybersecurity challenges where participants apply offensive and defensive skills – such as exploiting vulnerabilities, reverse engineering, or cryptography—to solve problems and retrieve hidden ‘flags’ for points) or bug bounty platforms (structured initiatives where organizations invite security researchers to identify and responsibly disclose vulnerabilities in their systems, offering financial rewards for valid findings) remained nascent throughout the 2000s, only gaining traction in the early 2010s. Red hacker groups filled this gap. Self-organized and technically rigorous, they developed skills through trial-and-error – often by probing real-world targets, driven by the belief that mastering offensive techniques is essential for effective defence.

While groups like the Honker Union and Green Army attracted thousands of users, it was their inner circles that drove real technical innovation and gave rise to the Red 40. These 40 technically advanced individuals played a central role in laying the foundations of China’s domestic cybersecurity industry.

Building the Industry

By the late 2000s, an increasing number of prominent red hacker groups fractured under growing pressure. Internally, many faced leadership disputes, diverging goals, and an aging member base. As one former Honker Union member put it, ‘Above all, most of us who were students had to find practical things to do after our graduation.’ Externally, the government had become increasingly wary of hacking group activities. The 2009 Criminal Law Amendment VII criminalized unauthorized intrusions and the distribution of hacking tools, leading to arrests and online forum closures.

Throughout the same period, China’s information and communications technology (ICT) sector was undergoing rapid growth, driven by telecom expansion, rising internet penetration, and the rise of major tech firms. This environment attracted many Red 40 hackers. Some founded cybersecurity start-ups, such as NSFOCUS and Knownsec, while others joined established cybersecurity firms such as Venustech and Topsec or helped build cybersecurity teams at Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent and Huawei.

Yet despite this growth, the cybersecurity industry remained underdeveloped. As Chinese tech outlet PingWest noted, ‘before 2010, cybersecurity had not received the attention it deserved from any perspective.’ The 2013 Snowden leaks marked a turning point. They confirmed long-standing fears of US surveillance and accelerated a national push to strengthen China’s cyber capabilities. Investment surged and regulatory frameworks were overhauled, boosting economic incentives by a lot. In this context, Red 40 led the transition into a new era.

By the mid-2010s, companies founded by Red 40 members, such as NSFOCUS and Knownsec, had become national leaders. Some Red 40 figures went on to lead cloud security efforts at major tech firms like Alibaba, Tencent and Huawei. Others launched startups in emerging fields such as APT tracking and cybercrime intelligence. Labs such as Tencent’s Keen Lab and Xuanwu Lab, led by Red 40 members, gained global recognition in vulnerability research through elite hacking competitions and bug bounty platforms.

Embedding into State Operations

As China’s cybersecurity industry matured in the 2010s, so did its ecosystem of highly sophisticated and persistent state-sponsored cyber actors, increasingly built around private-sector proxies. Parallel to their contributions to the private sector, Red 40 members have also become key figures in China’s state-sponsored cyber operations.

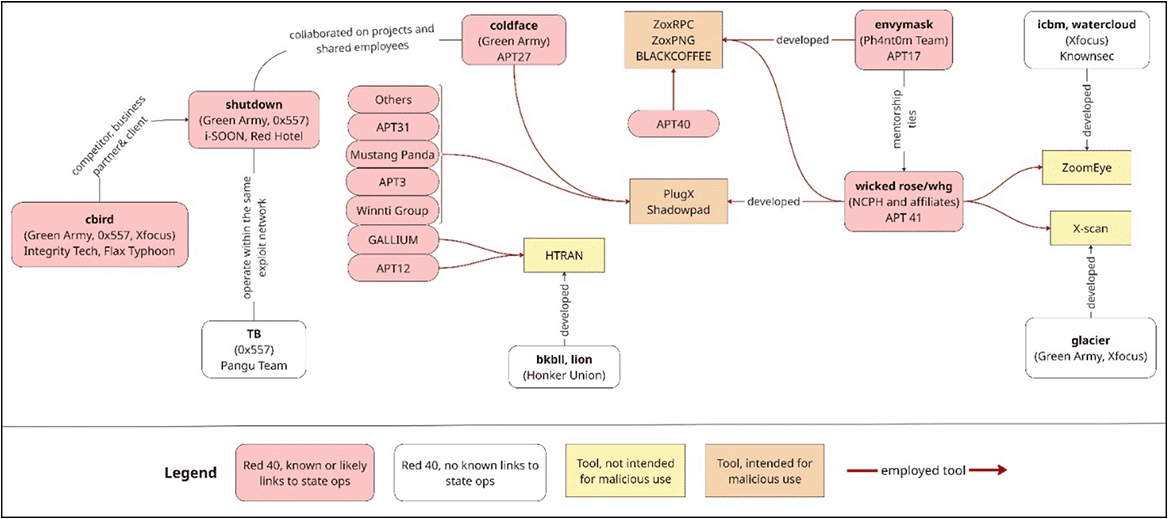

Figures such as Tan Dailin (wicked rose), Zeng Xiaoyong (envymask), and Zhou Shuai (coldface) transitioned from online forums to front companies conducting cyberespionage for government security agencies, becoming central actors in groups such as APT41, APT17, and APT27. From January to March 2025, not only front companies but also established firms led by Red 40 members have been linked to state-sponsored operations. Among them are i-SOON—led by Wu Haibo (shutdown) and Chen Cheng (lengmo) – and Integrity Tech, headed by Cai Jingjing (cbird).

These firms, which have associated with threat actors Aquatic Panda and Flax Typhoon –reportedly responsible for compromising victims within a wide range of industries globally – place a strong emphasis on commercial cybersecurity training. This distinction is important: unlike front companies, which often have minimal commercial activity and serve primarily as operational cover, real businesses are profit-driven, scalable and embedded in the broader cybersecurity sector. For instance, Integrity Tech leads China’s cybersecurity training market with a 20.4% share. Leveraging such firms enables more persistent, better-resourced and more innovative cyber capabilities.

Finally, many of the Red 40 members involved in state-sponsored operations were personally acquainted and maintained long-standing professional and informal networks that helped shape how talent and tools are shared across China’s APT groups.

From The Red 40 to the Next Generation

The Red 40 laid the foundation for what has since evolved into a structured and institutionalized cyber ecosystem, anchored by an industry increasingly driven by innovation in attack-defence capabilities. Unlike earlier generations who came of age reading hacker magazines and teaching themselves online, the country’s cyber workforce is now shaped by hacking competitions, specialized university programs, and attack-defence exercises. Today, companies rooted in capture the flag culture are regarded as a primary engine of innovation, offering offensive and defensive services like red teaming, penetration testing and threat intelligence.

Founders like Chen Peiwen (Boundary Unlimited), Kevin Shen (Yunqi Wuyin), and Shu Junliang (Feiyu Security) led top university CTF teams before launching startups built on offensive capabilities. Their firms focus on fuzzing, application security, and secure software development – fields where offensive skills offer a strategic edge. Others, such as Zhang Ruidong (NoSugar) and Yang Changcheng (Zhongan Netstar), apply similar techniques to fraud detection and law enforcement support. As this ecosystem grows, it likely plays an increasingly central role in enabling China’s APT activity, given the state’s growing use of private-sector actors to conduct cyber operations.

Conclusion

The story of China’s red hackers is a case study in how informal cyber communities, given the right incentives – can evolve into core enablers of state capability. The Red 40 didn’t merely staff China’s cybersecurity ecosystem; they shaped it from the ground up. As other nations consider how to cultivate cyber talent and strengthen public-private partnerships, China’s experience offers a powerful lesson: what begins in anonymous forums can end in boardrooms and on digital battlefields. Ignoring this emerging civilian talent comes with strategic risk.

© Eugenio Benincasa, 2025, published by RUSI with permission of the author.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

For terms of use, see Website Terms and Conditions of Use.

Have an idea for a Commentary you'd like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we'll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. View full guidelines for contributors.

WRITTEN BY

Eugenio Benincasa

Guest Contributor

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org