How can Coordinating Public, Private and People Help Reduce the Impact of a Grey-Zone Incident?

This article considers how to increase societal and governmental resilience in the UK to reduce the impact of an attack, whatever its nature.

Modern deterrence has been defined in various ways since the First World War, yet the aim remains the same: the ability to avert conflict. The ideal objective of modern deterrence is to be able to reduce the impact of an attack to the extent that it is not worthwhile for the adversary to attack in the first place. This concept has two significant attractions:

- The UK’s ability to respond is directly within its control, while influence over adversaries is not, so the UK should look internally at what can be controlled first.

- The impact of a ‘grey-zone incident’ – an event which significantly affects national security yet falls short of an all-out war – could be the same from natural causes as from malicious intent. Hence, greater resilience will serve the UK well in both cases.

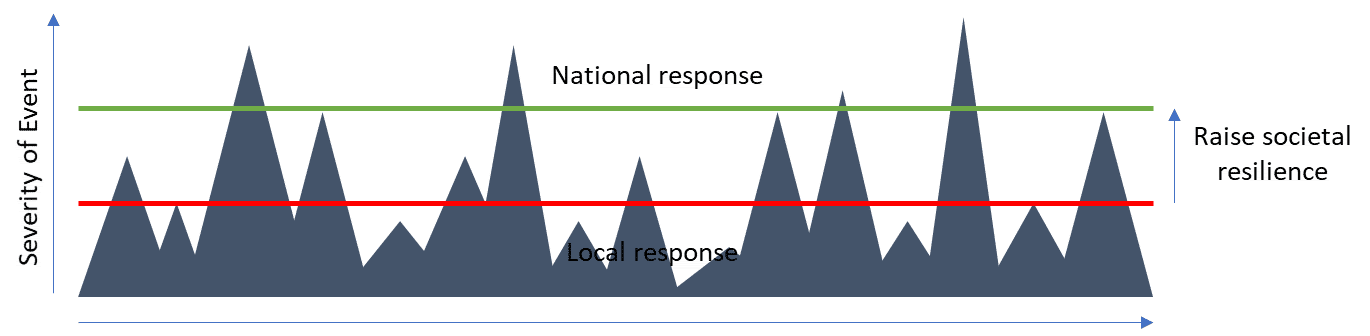

It is impossible to plan for every eventuality now, not least because technologies and threats (particularly in cyberspace) change so fast. Nor should the UK and its citizens try to; there is no crystal ball and any attempt to nail down every scenario and response will always be fighting the last war. Instead, the UK needs to build adaptable and responsive mindsets across public, private and individual actors, so that the basics are in place and to provide an adaptive response to any incident. This will reduce the ‘noise’ in the system by deterring an attack or making it have little or no impact, freeing up scarce specialist resources to focus on the national-level events that really need them.

So what needs to be done do to bring together the public and private sectors, and individuals across the UK, to reduce the impact of an incident?

There is a role for each, and the success of the relationship will be dependent on mutual trust and understanding.

In addition to the response from emergency services and the military to an attack, the government needs to lead in the preparation and structure of the overall UK response, and in determining how the resources of government, industry and individuals can be used most effectively. Much of this is, of course, in the planning and preparation before the event.

At the national level, the government needs to provide the oversight and framework for response as well as a consolidated view of threats and trends. This horizon-scanning and threat assessment, to develop realistic scenarios against which organisations can plan, should be done hand in hand with industry and society. The convening power of government and the knowledge of experts from organisations, such as the National Cyber Security Centre in cyber, are key to building a collective understanding and coordinated response.

Building trust and understanding between industry and government is essential to a coherent, blended response. There are good examples of relationship-building between government and industry from countries such as Finland, where the top 40 officials and industry leaders spend a week together once a quarter jointly developing the collective resilience of the nation. This both uses resources effectively and creates personal trust and buy-in. This is more complex in the UK, but if the top 1,000 industry leaders, particularly in the critical national infrastructure and technology, knew and trusted each other, this would be a great step towards making better use of collective resources.

The government also has a role in providing communication and guidance. A lack of good information will rapidly breed rumour, suspicion and dissent. The government needs to be ready to provide leadership and information in the event of an incident, and the media needs to be ready to help get the right messages out in the right way to keep society working together constructively – for example, pragmatic steps and balanced information provided rapidly across various media platforms.

There are also steps that companies can take to build their resilience by creating a local network of organisations that can help each other during and after an incident. This could be as simple as using each other’s offices, sharing information across the supply chain or sharing backup generators for emergency power. Establishing these networks also creates a group of individuals that know and trust one another. As the UK has seen from the last few years of cyber attacks, including TalkTalk as an early example, knowing whom to call and feeling that there is a network of support is psychologically powerful in enabling a rapid and effective response.

As humans respond more positively when they feel more in control, this has the double benefit of increasing local responsibility and control and limiting reliance on the central government responders. All of this reduces the stress on the national system in the event of a low-grade attack as companies can look after themselves and provide a support network to their ‘buddies’ and supply chain.

Individual ResponsesIndividuals need to be prepared to look after themselves and their community in the event of an emergency, such as the power grid going down, and take responsibility for their own reaction to information and the scepticism with which they view it. This isn’t going to happen overnight, of course, but initiatives in schools to educate youngsters on different kinds of incidents and what is entailed in a response, and to build on their naturally questioning minds to challenge the information they receive on social media, all go towards creating a society that can work together in a crisis. Latvia has launched precisely such a curriculum.

It may sound dramatic, but society is now so dependent on the continued supply of power, water, communications, food, medicine and banking, many on a just-in-time basis, that disruption to these systems, even for a short time, would severely impact day-to-day lives. Each person knowing how they would cope personally and what part they can play is essential to keeping the country running.

Whatever the nature of an attack or incident, the ability of the UK to respond and reduce the impact will allow scarce sophisticated response resources to be focused on the truly national-level events. The public and private sectors need to work together to build trust. Government and industry need to cooperate to set out a framework and guidelines that make best use of resources and enable industry to develop its own resilience networks. Individuals then also need to take responsibility for their own ability to manage through a crisis.

Collectively, this provides not just a more effective response but also a more engaged, empowered and confident society that can cope with minor incidents locally, leaving government and central organisations to focus on the national events that only they can handle.

Cate Pye is a cyber and security expert. She is due to join the team at PA Consulting, the innovation and transformation consultancy, in September.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.