Typhon, European Deterrence and Industrial Ambition for Deep Precision Strike

Typhon would put St Petersburg in reach of a German offensive mid-range capability, a leap for Germany's strategic culture. It should develop a European equivalent.

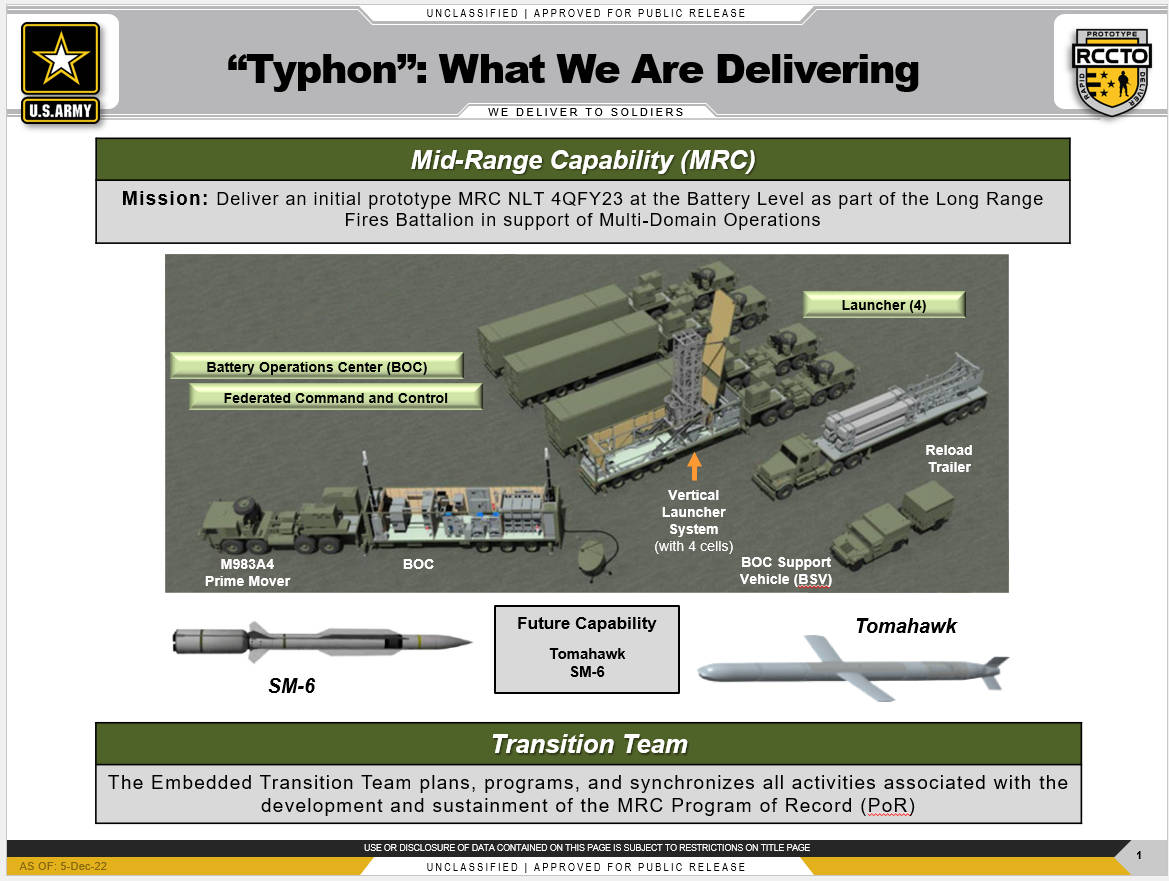

As far as naming missiles go, Greek mythology has been a thankful source for inspiration: the British Trident missiles allude to Poseidon’s weapon of choice, and the Aegis missile defence system invokes the shield of Zeus, to name but a few examples. In 2023, a new system joined the family: the ‘Typhon’ is a container-like trailer from which the US Army launches cruise missiles, Tomahawks, and ballistic missiles, SM-6s. Seeing the system in action, the namesake, a Greek monster, seems like an obvious choice.

Ancient tragedian Aeschylus described Typhon as a ‘destructive monster of a hundred heads, impetuous . . . hissing out terror with horrid jaws, while from his eyes lightened a hideous glare.’ The Lockheed Martin produced Typhon has capacity for 4 missiles, though their warheads should be more destructive than the monster’s 100. A battery of the system consists of four such launchers, a trailer-based Battery Operations Centre, as well as a trailer for reloading missiles. The missiles that Typhon launches have significant reach. The Typhon-adapted Tomahawk cruise missile has a range of up to 1500 km, while the SM-6 can reach targets of up to 320 km.

Europe badly needs a capability such as the one provided by Typhon. Under the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF), the US had agreed with Russia not to station intermediate range ground-launched missiles in Europe. The withdrawal of Russia and the US from the treaty in 2019 left Europe unprepared. It had not the capability to answer the significant build-up of intermediate range capabilities near its eastern flank.

Ground-based deep precision strike capabilities, however, are a necessary tool to deter Russia from aggression and escalation. They have the potential to disrupt supply chains far behind enemy lines, destroy command posts, attack strategic targets and even threaten second-strike capabilities. Launching them from the ground, instead of from ships (where they have been in use for a while), increases their potential reach, mobility and resilience. The truck-based units move faster than ships, making them harder to detect and attack. Their value to deter Russia from aggression is, therefore, high.

As most European allies, the German Bundeswehr has critical gaps in this deep-precision strike capability. It currently relies on the air-to-surface Taurus cruise missile with an estimated range of 700-800 km, with a reported stockpile of around 300 operational units. Not sufficient in terms of range, resilience and quantity by some margin, experts say. Ground based capability, ballistic missiles and faster cruise missiles would bolster the German mid-to-long range capability significantly and make it more resilient.

In this light, the German government acquired a taste for the monster. In a first step last year, it agreed to host a US Army Typhon battery stationed in Germany. This was a remarkable step for the government at the time. After all, the Social Democrats had fought an EU election campaign based on the promise to be careful around any escalation with Russia vis-à-vis its support for Ukraine.

The disarmament initiatives had long been a central pillar of Germany’s foreign policy, and hosting foreign missile systems was once enough to fracture entire governments: the decision to allow Pershing II deployments in the 1980s triggered mass protests and political upheaval. Yet, even as some well-known operators of the fringes of Germany’s political system began propagating against the decision, that criticism never matured into a societal scepticism. The warning that this may make Germany a target of Russian nuclear strikes was quickly defused by the reality that its role of a logistics hub in any confrontation between NATO and Russia would make it such a target anyways.

This remarkable coming-of-age of German defence-political debate was even more visible last week, when the German defence minister, Boris Pistorius went further and officially confirmed Germany’s interest to also purchase the Typhon. Ownership implies authority over when and how Typhon is used. And this use can deviate from what Germans have come to accept as the purpose of the Bundeswehr, defence of German soil. This is because the capabilities that Typhon enables can deter aggression through denial but also through punishment.

Deterrence by denial refers to making an enemy believe that one can negate the effectiveness of its offensive capabilities, which makes aggression less likely to have the desired outcomes and dissuades from such an aggression. Elaborate missile defence systems are one example, but long-range precision missiles also add to this form of deterrence, as they disrupt enemy supplies and C2. This is the kind of deterrence that Germans have come to accept as a necessary tool of solid defence strategy.

Meanwhile, deterrence by punishment refers to making the enemy count on a counterstrike against strategic targets upon their aggression, raising the stakes of that aggression for them. This form of deterrence depends on a resilient and therefore credible second-strike capability, conventional or otherwise. A ground-launched long-range missile capability such as the one enabled by Typhon can play a part in that form of deterrence. It could reach St Petersburg from eastern Germany, and Moscow when stationed further east in NATO or equipped with new missiles currently under development. This is unlikely the primary use-case of Typhon in contemporary German doctrine. But simply the fact that Russia may (and probably will) view the new capability from this perspective gives it a deterrent effect.

To maximise it, German strategic culture would need to evolve further, as deterrence by punishment only works if the attacked society shows the resolve to a retaliatory attack. For a nation in which, only a few years ago, it was a mainstream political question whether to continue the nuclear sharing arrangement with the US and replace the outdated German Tornados that would deliver nuclear retaliation against Russia, this is a significant step. In the case of Typhon, it appears that the military capability precedes society’s resolve of putting that capability to the most effective use. While unusual, it may be a good way to get the Germans used to their new geopolitical reality.

At the same time, the request by Pistorius also illustrates Germany’s current position on the question on how to rearm in the trilemma of an increasingly unreliable US ally, from which it has relied on for deep-precision strike capabilities, the urgent need for these capabilities, and the European industrial base’s need for time to develop indigenous equivalents to the US products.

The political challenge will be to go through with the plan, as other requirements arise, or new priorities are set

The European defence industry has recognised this need and is engaged in several initiatives to develop European ground-based solutions or to produce existing US solutions here. One example is Rheinmetall’s cooperation with Lockheed Martin to adapt the GMARS system, which would enable ground-based launches of Precision Strike Missiles (PRsM) and ATACMs, with ranges of up to 1000km and 300km, respectively.

Meanwhile, there is the European Long Range Strike Approach (ELSA) project, a group of European nations, France, Germany, Poland, Italy, the UK and Sweden that seek to develop a suite of mid-to-long range cruise and ballistic missiles. Yet, the new development of capabilities suffers from a key flaw: it is expected to be introduced at scale in the 2030s. When announced at the 2024 NATO summit, some may have seen the US stationing of Typhon in Europe as a possible bridge to speed up the development of an indigenous European solution. An impression fuelled by the fact that the day after the announcement, the Europeans signed a letter of intent on ELSA.

Some see the announcement that Germany also wants to purchase the Typhon for the Bundeswehr as a change in that calculus due to the new administration in Washington, DC. Indeed, US support for NATO seems uncertain, with Mr Trump alluding to the fact that military support depends on allies paying their fair share on defence. However, a purchase of Typhon cannot really moderate the alleged risk of US non-support, as the supply of missiles and the data that makes them effective is entirely dependent on US support. Instead, the purchase is a sign of the immediacy of the needs for such a capability in Europe, which are unlikely to be satisfied by the pledged US battery alone.

While experts have voiced doubts that Lockheed Martin would not be able to deliver anytime soon, the company vowed that it could deliver within a year of signing contracts. The Germans have few other choices then to trust those promises as they wait for a sovereign European capability. And the German decision is not singular: with purchases from the US and Korea, other European nations have shown that they will need to do both, fill immediate capability gaps and begin building the industrial capacity to satisfy long-term demand of missiles and the complex set of C4ISR capabilities that enable their effectiveness, even when the US is concentrating its forces elsewhere. The political challenge will be to go through with the plan, as other requirements arise, or new priorities are set. Years of neglect will not be fixed by always satisfying the next immediate needs at the cost of long-term planning. This requires foresight and, above all, fiscal resolve and patience.

© RUSI, 2025.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

For terms of use, see Website Terms and Conditions of Use.

Have an idea for a Commentary you'd like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we'll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. View full guidelines for contributors.

WRITTEN BY

Dr Linus Terhorst

Research Analyst

Military Sciences