Libya's Lessons for Venezuela: Reform the Economy Before It Is Too Late

Venezuela needs fundamental change to its economic structures to prevent the abduction of Nicolas Maduro from eventually leading to increased corruption and systemic violence.

Is the Trump Administration’s intervention in Venezuela an exercise in full-scale regime change, partial regime decapitation, or merely a police action? What are the likely pitfalls of each approach? Is the security situation on the ground in Venezuela likely to deteriorate and which social or economic structures might form a locus of resistance? These exact questions were debated on 8 January by Dr Jonathan Eyal, Arthur Snell, Jane Kinninmont and this author during our recent RUSI/Disorder live Podcast – listen here.

We concluded that neither President Trump nor Secretary Rubio appear to have concrete thoughts on an end game. Nonetheless, early signs indicate a mixed approach – partial decapitation of the old leadership, paradoxically leaving Maduro’s interior minister Diosdado Cabello in place – combined with a high degree of continuity of existing regime structures, with the primary economic changes limited to preferential access to oil assets for American firms. In line with this approach, President Trump’s press statements have thrown Venezuela’s internationally-acclaimed opposition figures under the bus, especially the Nobel Prize Laureate and Magnitsky Award winner Maria Corina Machado. Despite this, she is trying everything to court his favour, going even as far as giving her Nobel Laureate medal to Trump.

Conditions for Corruption

Despite the Administration’s lack of clarity on its post-conflict transition method, Trumpian commentators, as well as Secretary Rubio, have suggested that the upcoming transition will be much easier than previous regime change operations because Venezuela has underutilised oil resources, has an educated class of technocrats, and lacks sectarian divisions.

Sadly, that does not necessarily sound like a recipe for success. It sounds like a re-run of Libya’s failed post-2011 transition, which was initially thought by its proponents to be ‘easy’ because the country also lacked sectarianism and was awash in both western educated technocrats and underutilised oil assets. The problems in Venezuela are likely to be roughly similar to those Libya faced: subsidies and the illicit economy incentivise a continuation of a status quo which benefits incumbent powerholders.

Since initiating resource nationalism, it has been easier for the Venezuelan ruling class to buy off potential opposition than to figure out how to sustainably develop their country

Trump’s decision to stick by Delcy Rodriguez, Maduro’s Vice President (who is compliantly dolling out new oil contracts) rather than elevating a respected opposition figure (like Machado, who is reportedly begging for the job) apparently entails that the underlying economic structures of Venezuela will not be rewritten. These existing incentive structures in the Venezuelan economy have given rise to the gangs, smuggling networks and entrenched interests that will oppose rationalising the economy. If Libya is a harbinger, these pre-existing economic structures will likely lead to fragmentation and rival fiefdoms staffed by inveterately pro-status quo actors.

A Rentier's Lament

A quick look back at Venezuelan history can show us that it was its economic structures which presaged the corruption and venality of Chavez, Maduro and their cronies. [The below text and the underlying research derives from my book Libya and the Global Enduring Disorder (OUP 2021), pls consult pages 100-104 for the relevant citations].

Venezuela was the world’s first country to become an oil rentier state. After the discovery of oil in 1914, an aspiring strongman Juan Vicente Gómez seized upon the oil majors’ preference to deal with a clear power structure to cement his one-man rule. Then, during the Second World War and the Cold War, Venezuela cultivated an alliance with a string of American presidents, exploiting their fear of Communism to confront the American oil majors’ interests and achieve a greater share of its oil wealth.

Since initiating resource nationalism, it has been easier for the Venezuelan ruling class to buy off potential opposition than to figure out how to sustainably develop their country. Although such patronage politics arose in the aftermath of the discovery of oil, only since the collapse of the Soviet Union has appeasement metastasised into radical populism and indirect rentierism, roughly akin to the situation in Libya.

Venezuelan appeasement-based programmes that were theoretically intended to benefit the poor – like subsidising the price of petrol or giving preferential access to hard currency for the importation of basic foodstuffs – have given rise to criminal gangs and pressure groups that seek to take advantage of the loopholes these programmes create. As the regime has come under threat, the military has been given preferential access to subsidised goods and racketeering opportunities to secure their loyalty.

Like in Libya, once appeasement was adopted, it is devilishly difficult to undo. As such, it should have been the priority of a well-coordinated international community to prevent economically and geostrategically critical nations like Venezuela and Libya from falling into the appeasement abyss. This is an easier task prior to a regime decapitation.

Venezuela’s economic structures have facilitated waste by promoting inflation, smuggling and corruption just like Libya’s. During the 1980s, certain far-sighted Venezuelans wanted to safeguard their nation’s future and learn from the mistakes of the past. In 1989, a democratically elected government sought to reduce the subsidies on gasoline, devalue the bolivar and eliminate the most corrupt government agency – the Recadi, which was in charge of granting preferential access to subsidised dollars. The government adopted neo-liberal-style reforms that unleashed a wave of looting, riots and protests in Caracas that elicited a repressive backlash from the regime, together known as El Caracazo.

Failing to mobilise their supporters effectively, the government preferred to bash the skulls of protestors rather than making the case for the reduction in subsidies. The protests and the bungled response stopped the government from implementing economic reforms, which could have prevented future smuggling, corruption and state collapse.

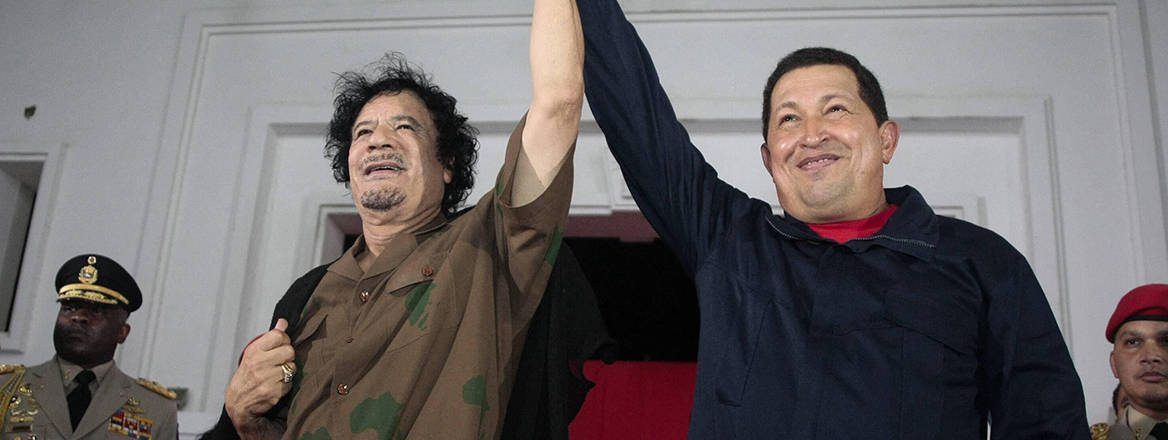

It was the shadow of democratic accountability, or the threat of removal from power, which led to, and perpetuated, the appeasement cycle in Venezuela, just as the threat of militias ousting the political class in Libya prevents them from cracking down on the militias’ avenues for enrichment. El Caracazo and the inability of globalist leaders to implement sane economic reforms contributed to the election in 1999 of the former coup-plotting paratrooper Hugo Chávez. He created and nurtured the self-reinforcing cycle of handouts, price controls and opportunities for regime insiders and the military to enrich themselves. Similarly to Gaddafi, while Chávez remained in power, the abuses of the system were kept within certain limits due to fear of his power and popularity.

Trump’s recent removal of Maduro is a decapitation of an already imploded regime. If Trump had wanted real change, he should have decapitated the corrupt economic structures, not kidnapped the President

Then, analogously to after Gaddafi’s fall, following Chavez’s death in 2013, the perversities of the economic structures he had created became fully apparent. Nicolás Maduro, Chávez’s successor as president, was no longer able to make sure that there were enough products in shops or petrol at the pump, as illegal gangs had arisen to smuggle these subsidised items out of the country. The gangs’ supporters had also infiltrated the ministries, just as Libya’s militias’ allies did. Appeasement had so weakened the Maduro government (just as it had the central authorities in post-Gaddafi Libya) that it attempted to ban the main opposition parties from taking part in the presidential elections, touching off a pernicious civil war from 2018 to the present.

Venezuelan appeasement was facilitated by a range of domestic and global pressures and led to the implosion of the Venezuelan state. Appeasement also sucked in foreign involvement by powers such as Cuba, Russia and Iran. One analysis of what has just happened with Trump’s recent removal of Maduro is a decapitation of an already imploded regime. If Trump had wanted real change, he should have decapitated the corrupt economic structures, not kidnapped the President.

The Need to Act

This then is the lesson that Libya can give to post-Maduro Venezuela: the economic structures of subsidies and semi-sovereign fiefdoms that gave rise to the colectivos must be eliminated prior to, not after, any attempt to transition to a fully new regime type.

Major economic reform has to happen now. But Delcy Rodriguez has no incentives to do so, she is both ideologically vested in the old system and she benefits from its patronage networks. Hence, if economic reform is not promptly pushed by Washington, British and European policymakers should brace for the rise of smuggling gangs and alliances between existing institutional heads and militias/colectivos.

Now is the time for think tanks to start studying the Venezuelan economy’s semi-sovereign economic structures and their direct connections to smuggling gangs, corrupt officials and security threats. The Trump Administration is unlikely to draw up coherent plans for root and branch reforms of the Venezuelan economy; it is too focused on taking a victory lap on social media and getting American oil majors in to secure the loot. British and European officials and think tanks, therefore, can now play a decisive role by proposing coherent market-based reforms to avert a violent scramble for the corrupt, subsidy-laden spoils.

© RUSI, 2026.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the author's, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

For terms of use, see Website Terms and Conditions of Use.

Have an idea for a Commentary you'd like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we'll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. View full guidelines for contributors.

WRITTEN BY

Jason Pack

RUSI Associate Fellow; Host of the Disorder Podcast

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org