Lake Malawi or Lake Nyasa? Malawi–Tanzania Border Dispute Slips Into Limbo

A dispute over the border between Malawi and Tanzania with its origins in the 19th century shows no signs of reaching a swift resolution.

The southern African country of Malawi is poor, with unstable neighbours. An insurgency has taken root in next-door Mozambique since 2017; it is struggling to cope with large numbers of arriving refugees; and its population has grown rapidly, to probably more than 20 million by this year. Moreover, climate change is bringing greater and more frequent destruction. These challenges make it more important than ever to maximise available resources.

Malawi also has a somewhat dormant border dispute with neighbouring Tanzania. In 2012, the issue came to the surface when Malawi’s then-President Bingu wa Mutharika saw an opportunity to investigate potential fossil fuel resources in the disputed area – under the lake that forms most of Malawi’s eastern border. However, because of the time and effort required to make the fossil fuel deposits profitable, and because of other issues preoccupying the Malawi government, little has actually changed as a result.

How did the dispute over the border arise? What has happened, and what is ultimately likely to happen in the future?

Origins

Lake Malawi or Lake Nyasa – the Malawi and Tanzanian name preferences, respectively – dominates the eastern border of Malawi. It is the third largest lake in Africa at 568 km long and sometimes stretches to a width of 80 km.

The 1890 Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty between Great Britain and Imperial Germany agreed the boundary between the then British colony of Nyasaland – now Malawi – and German East Africa, which in time became Tanzania. The treaty set the boundary along the Tanganyika side of the lake shore. The whole of the lake became part of Nyasaland. But these decisions were taken without consulting Africans, who should have had a say. They created more problems in Africa than they solved. People living around the northern shores of the lake are very much related. They speak the same language, have the same culture, and share the same beliefs. Today’s challenge – who owns the lake – would not have existed at all were it not for the treaty.

The lake constitutes about a third of the entire territory of Malawi. Malawi’s economic life, culture, folklore and national sentiment are indistinguishably linked to the lake. Tanzania, too, derives considerable value from the lake. It has navigation and fishing rights; the lake supports a large number of artisanal fishermen; and there are ancestral burial places that now lie under the water.

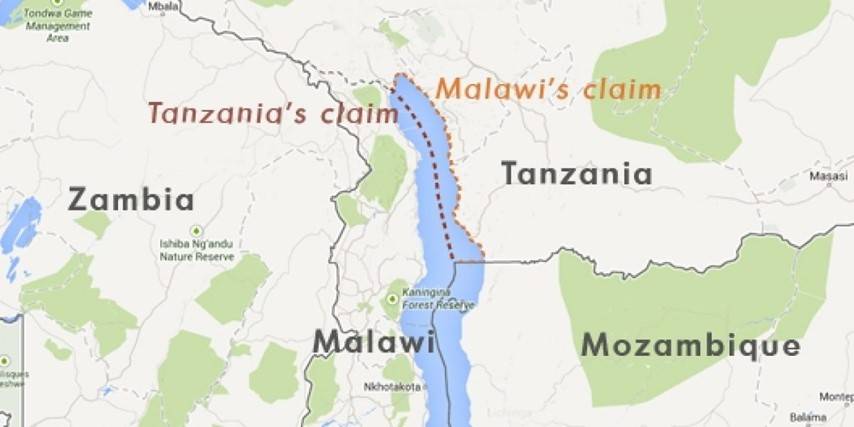

There were brief arguments between the two states’ officials in 1967–68, with no clear outcome. Malawi’s view was that the boundary follows the lake shoreline in accordance with the 1890 Heligoland Treaty. Tanzania sought recourse to the international legal rule that ‘boundaries at lakes are divided [at] the median line’. Thus, Tanzania argues that it should own half the lake (see the map above). Tanzania has also made arguments on the basis of its fishing economy, historical claims, and the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Yet Tanzania’s challenge to the treaty was not actively pursued as government policy, and it effectively lapsed. Instead, in line with the Cairo Declaration, Tanzania recognised the general continuing validity of African borders as they had been at independence. Tanzania’s first president, Julius Nyerere, conceded the boundary.

Re-Emergence

Malawi is connected to international markets through four key ports: Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, Beira and Nacala in Mozambique, and Durban in South Africa. Tanzania has become a lifeline for Malawi, and it cannot afford to have sour relations with the country. So far, Malawi has not had any trouble on this front. Life goes on, and Tanzanians and Malawians continue to cross the border, selling and buying products.

The border issue resurfaced this century because of strong indications that fossil fuels might lie under the lake. In October 2011, Malawi President Bingu wa Mutharika awarded a UK company a contract to start oil and gas exploration in the eastern part of the lake. The contract included exploration within the Tanzanian-claimed area. Despite Tanzanian protests, Malawi refused to stop. President Bingu wa Muthrika then died in office in April 2012. But Peter Mutharika, Bingu wa Muthrika’s brother, subsequently became president in 2014. He was also interested in furthering the search for oil and gas under the lake.

The two parties submitted the dispute to mediation by the Southern African Development Community (SADC). SADC appointed former Mozambican president Joaquim Chissano as chief mediator, alongside former South African and Botswana presidents Thabo Mbeki and Festus Mogae. In 2017, the mediators gave the disputants three months to come to a final resolution after both countries stuck to their positions. The team held its last negotiations in July 2017; a meeting in 2018 was cancelled at the last minute. But then the dispute lost urgency. In both 2019 and 2020 the Malawi and Tanzanian presidents, meeting together, said the two countries’ relationship was cordial. New Malawi President Lazarus Chakwera said the dispute was a non-issue.

Although greater energy resources would be helpful for Malawi, if its good relations with Tanzania were to be destroyed as a result, the costs might well outweigh the benefits

In the two-and-a-half years since, Malawi has worked on diversifying its oil supply routes via Mozambique. Significant political controversies have also emerged. There have been splits in the governing coalition, and a number of scandals that have reached President Chakwera’s allies, as well as problems with subordinate ministers. Martha Chizuma, the director of the Anti-Corruption Bureau, has been pushing her work with a verve that has caused considerable consternation.

More recently, in March 2023, Malawi was hit by Tropical Storm Freddy. Initial reports indicated that 200 had been killed, but the death toll may rise to 1,200. Malawi’s somewhat limited resources are likely to be further stretched, as its reliance on agriculture and high disease burden leave its poor population extremely vulnerable to climate shocks. Weather-related disasters have been increasing in number for nearly 50 years, since 1974.

Conclusion

Extracting fossil fuels from under the lake would take significant time and effort. The Malawi government is preoccupied by a number of other major issues at present, and climate change will exacerbate many of these challenges. As a result, the border dispute has again entered a state of limbo.

As a poor country, greater energy resources would be helpful for Malawi. But if its good relations with Tanzania were to be destroyed as a result, the costs might well outweigh the benefits. The dispute currently appears to be at a standstill, pushed to the bottom of the agenda by a host of other more pressing concerns. As a result, nothing fundamental is likely to change any time soon.

This piece draws on a 2020 policy paper by Brigadier General Chirwa’s Centre for Peace and Security Management in Lilongwe, Malawi. Visiting Malawi, Dr Robinson saw the opportunity to promote southern African analysis. He updated, summarised and edited the text to match RUSI’s requirements.

The views expressed in this Commentary are the authors’, and do not represent those of RUSI or any other institution.

Have an idea for a Commentary you’d like to write for us? Send a short pitch to commentaries@rusi.org and we’ll get back to you if it fits into our research interests. Full guidelines for contributors can be found here.

WRITTEN BY

Brigadier General (Retd) Marcel R D Chirwa

Dr Colin Robinson

- Jim McLeanMedia Relations Manager+44 (0)7917 373 069JimMc@rusi.org